Author: Nick Maggiulli, Finance Blogger & Author of "Just Keep Buying"

Compiled by: Felix, PANews

Original Title: A Century of U.S. Stock Market Revelations: Why We Should Chase Beta and Forget Alpha

The investment world widely believes that alpha, or the ability to outperform the market, is the goal investors should pursue. This is entirely logical. All else being equal, more alpha is always better.

However, having alpha does not always mean better investment returns. Because your alpha always depends on the market's performance. If the market performs poorly, alpha may not necessarily bring you profits.

For example, imagine two investors: Alex and Pat. Alex is very skilled at investing, outperforming the market by 5% every year. Pat, on the other hand, is a poor investor, underperforming the market by 5% each year. If Alex and Pat invest during the same period, Alex's annual return will always be 10% higher than Pat's.

But what if Pat and Alex start investing at different times? Is it possible that despite Alex's superior skills, Pat ends up with higher returns than Alex?

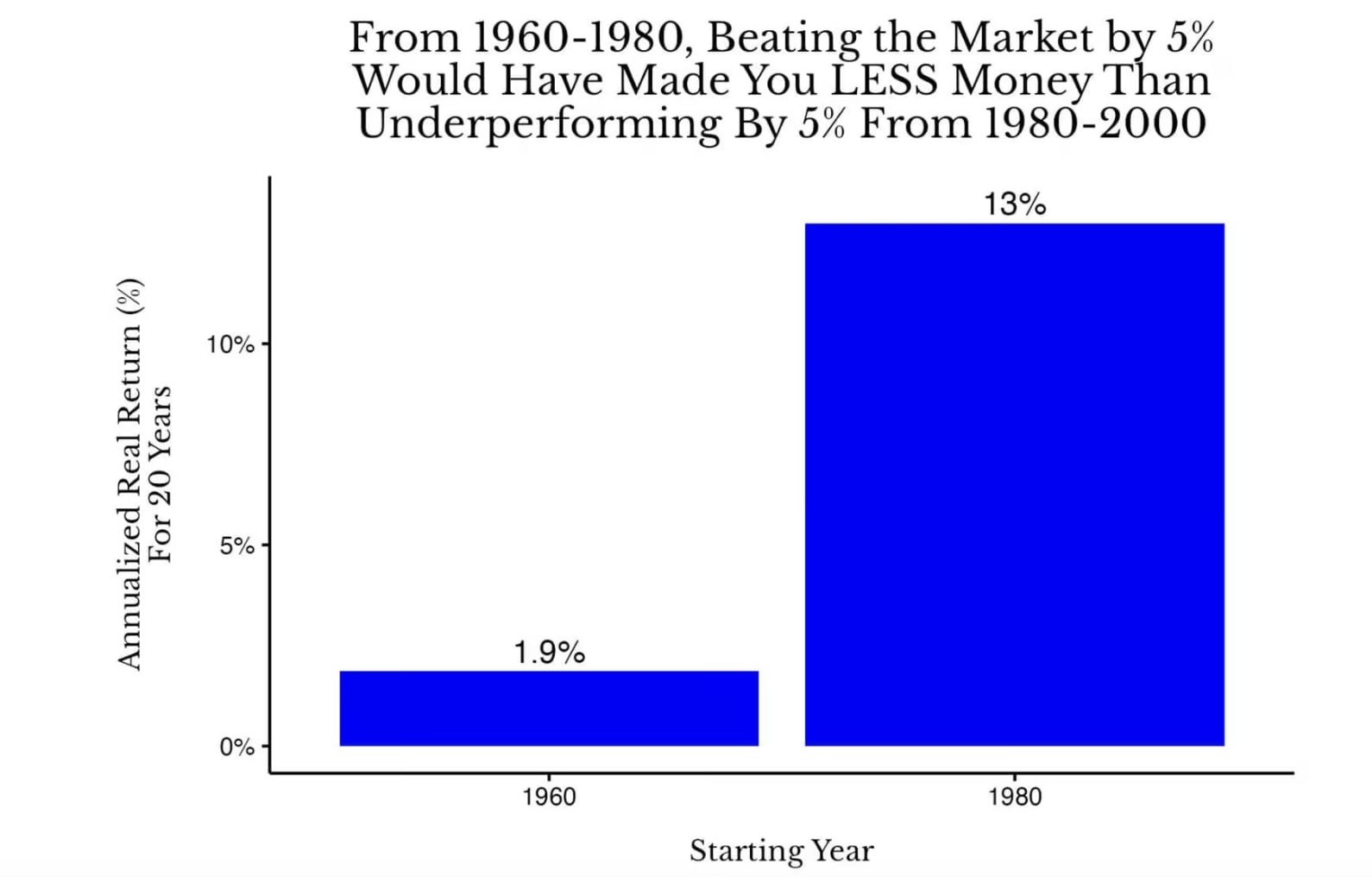

The answer is yes. In fact, if Alex invests in U.S. stocks from 1960 to 1980, and Pat invests from 1980 to 2000, then after 20 years, Pat's investment returns will exceed Alex's. The chart below illustrates this:

In this scenario, Alex's annual return from 1960 to 1980 is 6.9% (1.9% + 5%), while Pat's annual return from 1980 to 2000 is 8% (13% – 5%). Although Pat is a less skilled investor than Alex, in terms of inflation-adjusted total returns, Pat performs better.

But what if Alex's competitor is a true investor? Now assume Alex's competitor is Pat, the person who lags the market by 5% each year. But in reality, Alex's true competitor should be an index investor who earns returns equal to the market each year.

In this scenario, even if Alex outperforms the market by 10% annually from 1960-1980, he would still lag behind an index investor from 1980-2000.

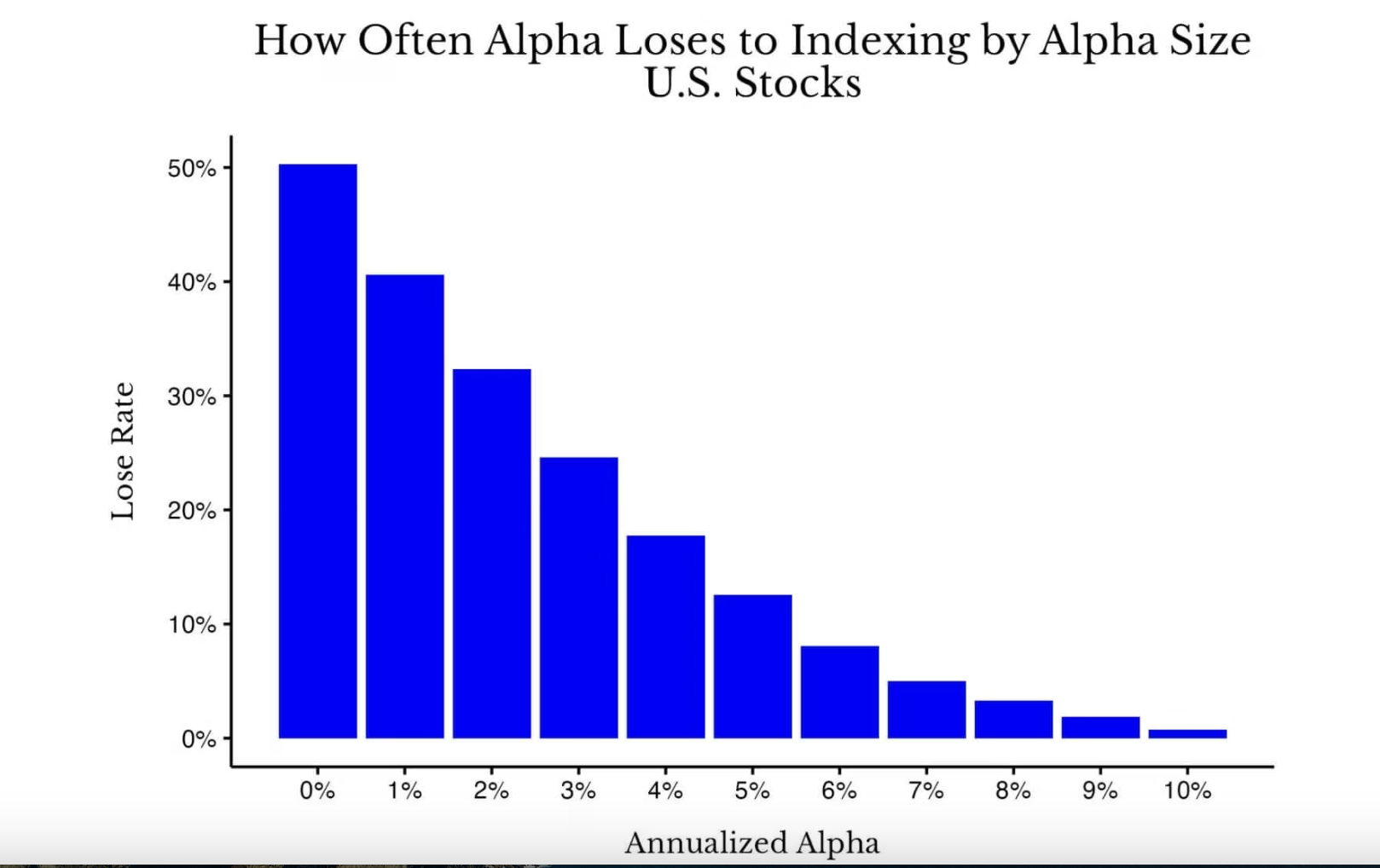

Although this is an extreme example (an outlier), you might be surprised how frequently having alpha leads to underperformance relative to historical periods. As shown in the chart below:

As you can see, when you have no alpha (0%), the probability of outperforming the market is essentially a coin flip (about 50%). However, as alpha increases, the compounding effect of returns does reduce the frequency of underperforming the index, but not as much as one might think. For example, even with an annual alpha of 3% over a 20-year period, there is still a 25% probability of underperforming an index fund during other periods in U.S. market history.

Of course, some might argue that relative performance is what matters, but I don't share that view. Ask yourself: would you rather have average market returns during normal times, or just "lose less money" (i.e., achieve positive alpha) during a great depression? I would certainly choose the index returns.

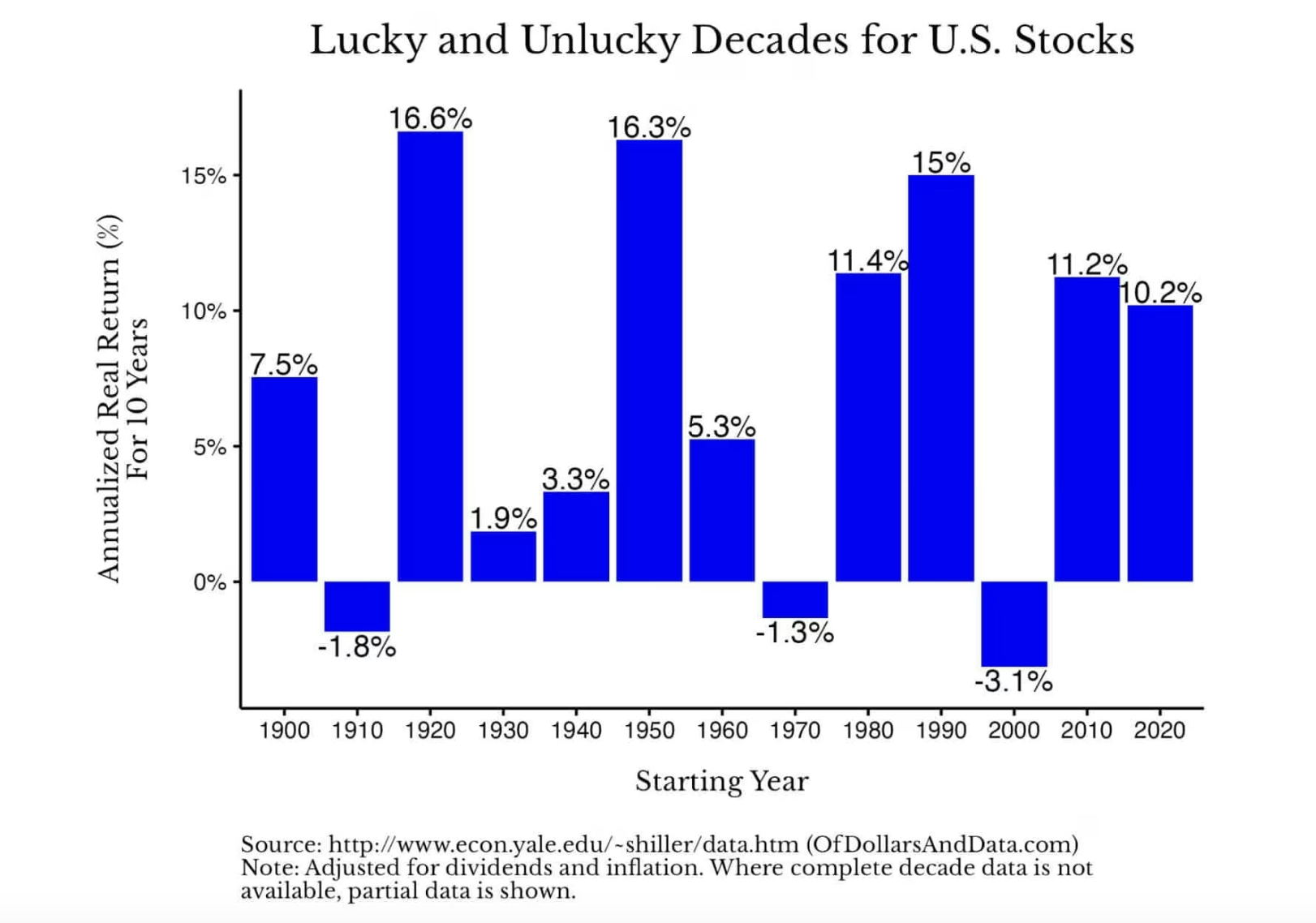

After all, most of the time, index returns deliver fairly good results. As shown below, the annualized real returns of U.S. stocks fluctuated by decade but were mostly positive (Note: Data for the 2020s only shows returns up to 2025):

All of this shows that while investment skill is important, market performance is often more critical. In other words, pray for Beta, not Alpha.

Technically, β (Beta) measures the volatility of an asset's returns relative to the market. If a stock has a Beta of 2, it is expected to rise 2% when the market rises 1% (and vice versa). But for simplicity, market return is often referred to as Beta (i.e., a beta coefficient of 1).

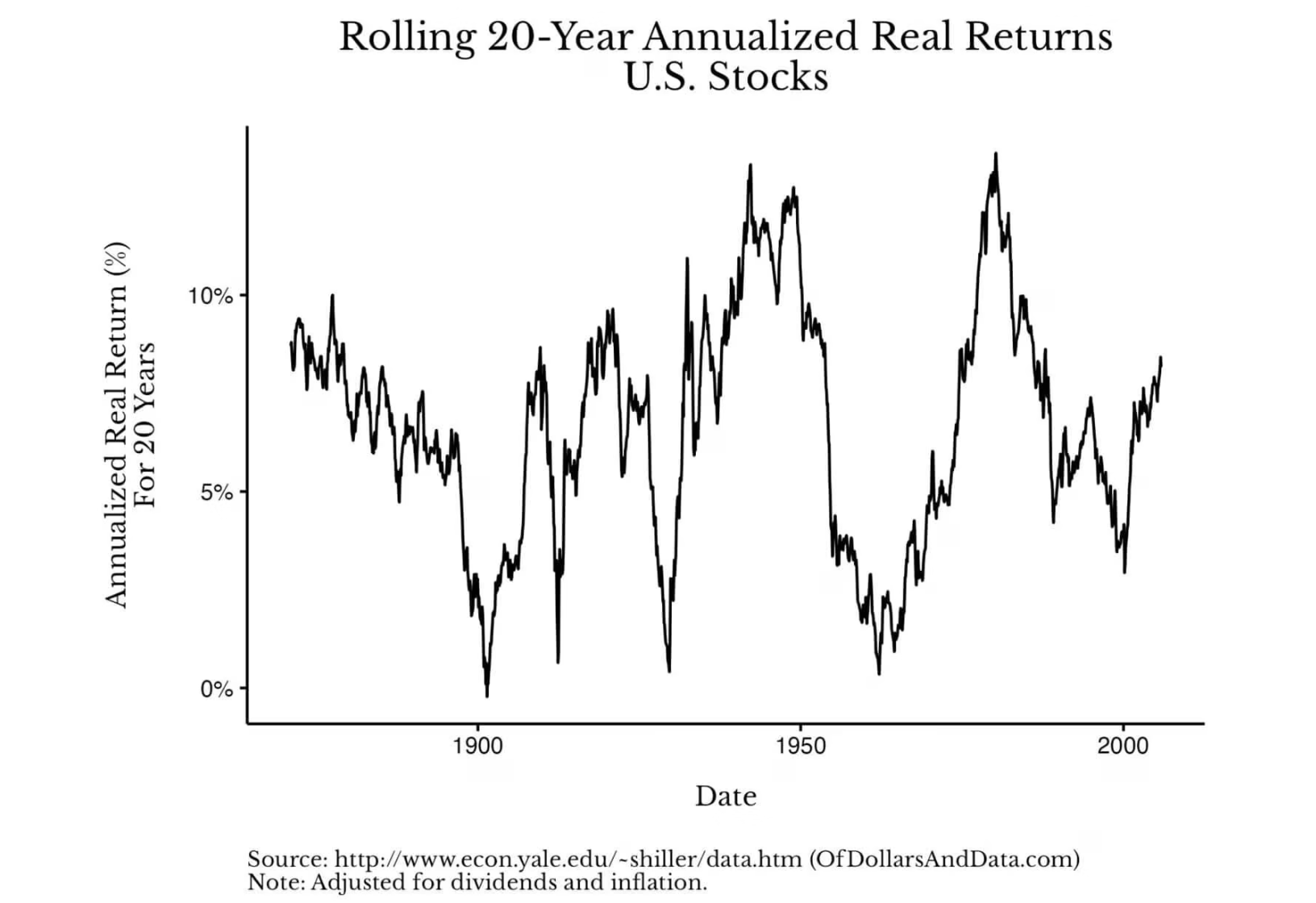

The good news is that if the market doesn't provide enough "Beta" in one period, it may make up for it in the next cycle. You can see this in the chart below, which shows the 20-year rolling annualized real returns of U.S. stocks from 1871 to 2025:

This chart visually shows how returns can rebound strongly after downturns. Taking U.S. stock history as an example, if you invested in U.S. stocks in 1900, your annualized real return over the next 20 years would be close to 0%. But if you invested in 1910, your annualized real return over the next 20 years would be about 7%. Similarly, if invested at the end of 1929, the annualized return was about 1%; whereas if invested in the summer of 1932, the annualized return was as high as 10%.

This huge difference in returns again confirms the importance of overall market performance (Beta) relative to investment skill (Alpha). You might ask, "I can't control where the market goes, so why does this matter?"

It matters because it is a relief. It frees you from the pressure of "having to beat the market" and allows you to focus on what you can truly control. Instead of feeling anxious that the market is beyond your command, see it as one less thing to worry about. See it as a variable you don't need to optimize because you simply cannot optimize it.

So what should you optimize instead? Optimize your career, savings rate, health, family, and so on. Over the long span of life, the value created in these areas is far more meaningful than苦苦追求 a few percentage points of excess returns in your investment portfolio.

Do the simple math: a 5% raise or a strategic career transition can increase your lifetime income by six figures or more. Similarly, maintaining good health is efficient risk management, significantly hedging against future medical expenses. And spending time with family sets a positive example for their future. The benefits of these decisions far exceed the gains most investors can expect from trying to outperform the market.

In 2026, focus your energy on the right things. Chase Beta, not Alpha.

Twitter:https://twitter.com/BitpushNewsCN

Bitpush TG Discussion Group:https://t.me/BitPushCommunity

Bitpush TG Subscription: https://t.me/bitpush