Federal employees were successfully reduced by 271,000, a decrease of 9%, setting the largest peacetime layoff record. However, at the same time, total federal expenditures did not decrease but instead increased, soaring from $6.75-7.135 trillion in 2024 to $7.01-7.6 trillion, a net increase of $248-480 billion. This phenomenon of "losing weight but gaining mass" is the core contradiction of the DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) reform.

This "external advisor" agency, initially led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, promised to use commercial means to dismantle government bureaucracy, cut redundant regulations, reduce wasteful spending, and ultimately save $2 trillion to balance the federal budget. This ambitious plan was expected to last until July 2026, giving them 18 months to transform the government. However, reality proved far harsher than expected: Musk resigned hastily in May, serving only a 130-day term as a special government employee; by November, DOGE quietly dissolved, a full 8 months before the original term was set to end.

This was not an unfinished reform, but a complete abandonment. From launch to disappearance, DOGE's actual lifespan was only about 10 months. When the savings target was clearly unattainable, legal challenges ensued, and disputes with Trump became public, Musk chose to return to his business empire, leaving behind a crumbling agency and a host of unanswered questions. This rapid fall from ambition to disillusionment exposed not only missteps in reform strategy but also the essential, difficult-to-cross chasm between corporate logic and government operations.

I. The Grand Vision vs. The Harsh Reality: A Complete Divergence

DOGE's reform vision was full of Silicon Valley-style idealism. They planned to use lean management principles to terminate hundreds of billions of dollars in inefficient contracts, close redundant facilities, reduce the federal workforce from about 3.015 million to a leaner size, and replace some bureaucratic functions with AI and automation tools. This methodology has proven successful time and again in the business world—why couldn't it be used to transform the government?

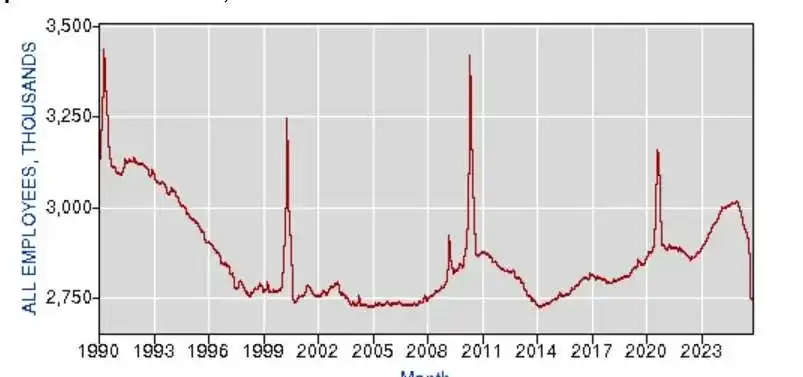

Chart: Federal Employee Count Since 1990

In January 2025, Musk joined DOGE as a special government employee, with a term set for 130 days. In Silicon Valley, 130 days is enough to launch a product prototype, complete a round of financing, or even turn around a startup's fate. In the initial months, DOGE demonstrated dazzling execution. From January to November, federal employees decreased from 3.015 million to 2.744 million, a net reduction of 271,000 positions. This was not only the largest peacetime federal layoff since WWII, but the speed of execution was also staggering. Specific actions included terminating a $290 million refugee facility contract at the Department of Health and Human Services, $190 million in IT redundancy spending at the Treasury Department, and closing hundreds of inefficient agencies and programs, cumulatively undertaking over 29,000 reduction actions. DOGE claimed these measures saved approximately $21.4-25 billion, primarily concentrated in non-defense federal mandatory spending, which decreased by 22.4% year-on-year.

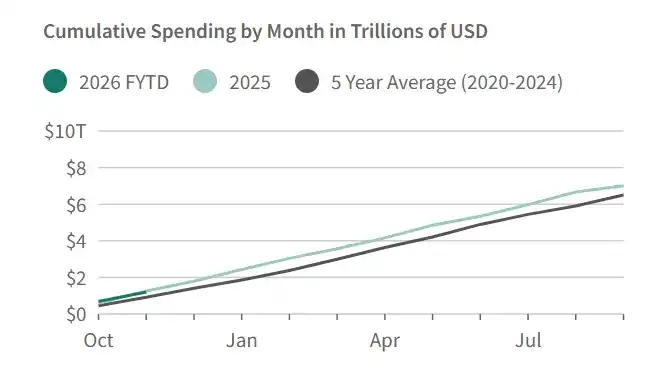

Chart: Cumulative Federal Government Expenditure

But the data on the spending side told a completely different story. Overall federal expenditure rose from about $6.75-7.135 trillion in 2024 to about $7.01-7.6 trillion in 2025, an increase of 4%-6%. Spending in just the first 11 months reached $7.6 trillion, $248 billion more than the same period the previous year. More ironically, some independent analyses suggested that DOGE's claimed savings figures might be severely inflated, with verifiable savings potentially only in the tens of billions, even as low as $3 billion. Due to the weakening of IRS enforcement capabilities, this could lead to at least $350 billion in lost tax revenue over the next decade, making the net effect of the so-called "savings" close to zero or even negative.

Resistance from reality soon became apparent. Federal spending continued to climb; mandatory spending like Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the national debt was completely unaffected by administrative layoffs. By May, multiple pressures converged. Musk's relationship with Trump began to deteriorate, with public disputes between the two. Legal challenges followed, questioning DOGE's authority and procedural legality. Tesla's business was also calling him back—stock price fluctuations, production issues, market competition, all requiring the CEO's attention. Most crucially, the $2 trillion savings target was clearly an impossible mission; staying on a project doomed to fail held no benefit for Musk's personal brand. As soon as his 130-day term ended, Musk announced his return to private enterprise. He did not apply for an extension, did not ask for more resources, but chose a clean break. This decision itself was the loudest admission: transforming the government with business methods was far more difficult than he had thought.

II. The Struggles of the Headless Horseman: Decline from May to November

After Musk's departure, DOGE tried to prove it could continue. The White House signaled that the "DOGE spirit" would be integrated into the government's daily operations, becoming part of the "government lifestyle." Some former DOGE employees were embedded in various federal agencies to continue pushing layoffs and cost cuts. Ramaswamy was still nominally leading the agency, trying to maintain the reform momentum.

But DOGE without Musk was like a rocket without an engine; inertia could only last so long. Without the star founder's halo, the agency's attention rapidly declined. Without Musk's direct communication channel with Trump, DOGE's influence within the government was greatly diminished. More importantly, the limitations of the reform became increasingly apparent—those large expenditure items that truly required Congressional legislation to change were utterly beyond DOGE's reach.

During this period, DOGE's achievements became harder to define. Although some layoff actions continued, spending data kept rising. Reports of service disruptions began to increase. Social Security applications were delayed, regulatory gaps appeared, and key positions were left unfilled due to over-cutting. Criticism grew louder: in the name of optimizing efficiency, DOGE was undermining the government's basic operational capacity. Legal challenges also accumulated, questioning whether many of DOGE's actions exceeded executive authority.

By November, several authoritative media outlets began reporting a fact: DOGE had quietly disbanded. Reuters, TIME, CNN, Newsweek, and others used terms like "disbanded," "quietly shut down," and "no longer exists" to describe the agency's fate. There was no formal dissolution announcement, no press conference; DOGE simply vanished from public view. Its charter, originally meant to last until July 2026, was terminated early, with many functions transferred to the Office of Personnel Management or other常规 agencies.

This silent end perhaps speaks volumes more than any failure. Not even a decent farewell, because admitting failure itself was an embarrassment. DOGE went from a revolutionary agency promising to change the government to a brief interlude everyone wanted to forget as quickly as possible.

III. The Underlying Logic of "Reducing Staff Without Saving Money"

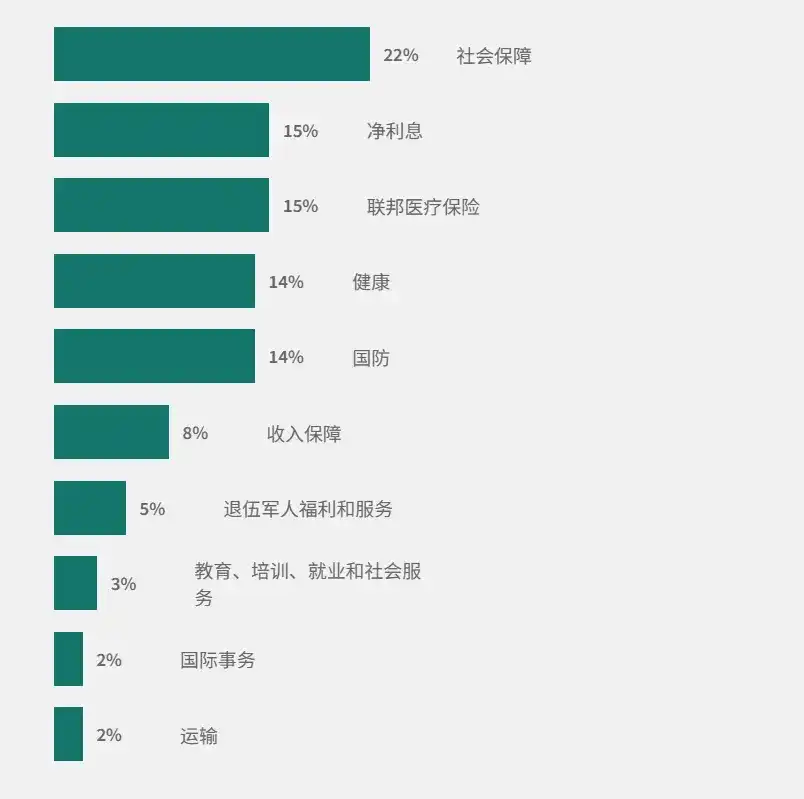

1. The Impenetrable Wall of Mandatory Spending

The most fundamental difference between the government fiscal system and a corporation is that over 70% of federal spending is on mandatory programs. These expenditures grow automatically as mandated by law, influenced by demographics, economic cycles, and interest rate fluctuations, completely unaffected by administrative layoffs. The 2025 data clearly shows this rigidity: benefit spending like Social Security and Medicare increased by about $168 billion, driven mainly by an aging population and inflation adjustments; national debt interest costs soared by $71 billion, with the debt scale already expanded to $36-38.3 trillion, making interest expenditure even exceed the defense budget, becoming the federal government's largest single expense.

These rigid expenditures directly offset all of DOGE's savings efforts. No matter how many administrative staff were cut, Social Security payments still had to be made according to statutory formulas, Medicare subsidies still had to be paid based on enrollment, and national debt interest had to be paid on time to maintain national credit. As an executive agency, DOGE could not unilaterally modify benefit programs authorized by Congress, meaning the effort was confined to the "periphery" from the start, unable to touch the "core" of expenditures.

At a deeper level, this rigidity stems from constitutional and legislative frameworks. The government is not a profit-seeking enterprise but a public institution承担ing the function of a social safety net. When a 65-year-old applies for Social Security, the government cannot refuse payment for "cost optimization." This is the essential difference between government and business, and the fundamental reason corporate thinking hit a wall here.

2. The "Offsetting" of Inter-Departmental Spending

DOGE did achieve some results in the discretionary spending area. They terminated 5,200 projects and hundreds of billions of dollars in contracts in departments like Health and Human Services, Education, and the Agency for International Development, saving about $37 billion. But these savings were quickly吞噬ed by growth in other departments. Defense spending increased due to geopolitical tensions, infrastructure investment膨胀ed due to the Trump administration's priorities, and the spillover effects of mandatory spending further pushed up the overall budget.

The result was "local slimming, global expansion." This is similar to the "savings transfer" phenomenon common in corporate mergers and acquisitions—costs cut in one department often reappear in another form elsewhere. But the government lacks the flexible adjustment mechanisms of a company and cannot reconfigure resources as quickly. The 2025 spending growth also included emergency response (increased natural disaster funds) and inflation adjustments (CPI rose about 3%-4%), these external factors further amplified the "offsetting" effect.

Specific data shows that DOGE's savings accounted for only 0.3%-0.5% of total spending, far insufficient to reverse the overall trend. In 2025, mandatory spending increased by $221 billion, discretionary spending increased by $80 billion, and net interest costs increased by $71 billion. When you save a few billion in one pocket but pull out hundreds of billions from three others, the so-called "efficiency improvement" becomes a numbers game.

3. The Cost Inertia and Transition Friction of Agency Operations

Layoffs are never a zero-cost operation, especially in the government system. Implementing the DOGE reform itself generated huge expenses: severance pay, paid leave, rehiring costs after wrongful termination, totaling an estimated $135 billion. This figure already far exceeds many of the "savings" projects claimed by DOGE. More hidden costs came from productivity losses and service disruptions.

The operation of government agencies highly relies on institutional memory and human networks. When large numbers of experienced employees left, Social Security applications began to delay, regulatory gaps appeared, and policy implementation efficiency actually decreased. Although AI and automation were held in high hopes, these tools are far from mature enough to completely replace human judgment. Algorithmic governance might be efficient, but it also brings new problems like data privacy leaks and algorithmic bias. In the process of transitioning from a "public service apparatus" to a "data-driven terminal," the government is losing something difficult to quantify but crucial—legitimacy, social cohesion, and public trust.

A more practical problem is the increase in overtime pay for remaining employees and rising contract outsourcing costs. The government outsourced work previously done internally to private contractors, often at a higher price. In the long run, large-scale brain drain could create a "knowledge gap," affecting policy continuity and professional capacity accumulation.

Conclusion: Who Lost? Reflecting on the Cost and Boundaries of Reform

In this collision of ideals and reality, who ultimately lost? Perhaps first the idealistic reformers, who underestimated the complexity of government operations and mistakenly thought business logic could be directly transplanted into the public sector. Taxpayers might benefit from partial savings in the short term, but face the risk of service cuts and quality decline in the long run. Beneficiaries of public services, especially groups relying on Social Security and Medicare, might suffer from service disruptions and reduced efficiency.

The deeper loser might be the entire system's sustainability and democratic legitimacy. When the government is "optimized" like a business, those values that cannot be measured by numbers—fairness, stability, social cohesion—are quietly being eroded. Opinion polls showed DOGE's approval rating hovering around 40%, reflecting public recognition of efficiency gains coexisting with concerns about service disruptions.

But this collision was not entirely meaningless. If DOGE can push Congress to take action and truly touch core issues like welfare reform and debt control, it could still become a historical turning point. The key is to recognize that the government is not a business; efficiency needs to be balanced with fairness, sustainability, and democratic principles. A business can sacrifice everything for profit, but the government must保留 the last line of defense for society's most vulnerable groups. This is the most important lesson corporate thinking needs to learn, and the most profound insight left to us by this激烈 collision.

Data for this report was compiled and edited by WolfDAO. Please contact us if you have any questions for updates;

Author: Nikka / WolfDAO ( X : @10xWolfdao )