When a city uses yesterday's rules to welcome tomorrow's innovations, it is destined to be lost today.

Today's Hong Kong is shrouded in a profound sense of division. Or rather, it is more like two Hong Kongs in parallel universes, folded into the same city.

One Hong Kong is in the skyscrapers of Central.

In 2025, Hong Kong's economy performed strongly, with real GDP growth for the year projected to reach 3.2%. The Hang Seng Index rose by 27.8%, marking its best annual performance since 2017. The value of merchandise exports hit a record high, with a single-month export value of HK$512.8 billion in December, a year-on-year increase of 26.1%. Net capital inflows remained robust, and the scale of private wealth management surpassed the HK$10 trillion mark.

Here, the sound of champagne bubbles is endless, and prosperity is the only theme.

The other Hong Kong is in the co-working spaces of Cyberport, on the streets of Sham Shui Po, at the crowded Lok Ma Chau Control Point.

Entrepreneurs struggle to sustain their businesses under the weight of high costs; in sectors like retail, store closures are frequent; the unemployment rate showed a gradual upward trend in 2025; and more and more Hong Kong residents are turning their backs on the former "shopping paradise" to spend their money in Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

Here, a sense of loss and confusion is the persistent background noise in the air.

On one side, financial data suggests roaring success; on the other, the public sentiment feels like treading on thin ice. This extreme contradiction is the most accurate portrayal of Hong Kong's current reality. Hong Kong is living off its past glory, trying to use yesterday's playbook to cope with today's new changes—the result is plain to see.

Two Crises and Muscle Memory

The rules Hong Kong follows today were forged from two painful lessons: the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Tsunami. These two events hurt Hong Kong deeply, leaving it scarred and fearful. It developed a muscle memory: at the first sign of risk, its instinct is to pull back.

In 1997, shortly after its handover, Hong Kong became a target for international speculators, led by George Soros's Quantum Fund. They shorted the Hong Kong dollar with one hand and Hong Kong stocks with the other, aiming to break the currency peg. A fierce battle, known as the "Hong Kong Financial Defense War," ensued.

Former Financial Secretary Donald Tsang later recalled it as an almost suffocating period. The Soros-led funds set a trap linking the stock and currency markets through shorting and borrowing. They massively sold Hong Kong dollars in the forex market, forcing the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) to raise interest rates to maintain the peg. Higher rates inevitably led to a stock market fall, allowing them to cash out their massive pre-positioned short positions. The net was closed, turning the stock and currency markets into their dual ATMs.

Initially, the Hong Kong government was losing ground. But on August 14, 1998, it decided to intervene directly in the market using its foreign exchange reserves. Over the next ten trading days, the government invested a cumulative HK$118 billion (approx. US$15 billion), confronting the speculators head-on.

On August 28, the settlement day for Hang Seng Index futures, the daily turnover of the Hang Seng Index reached a record HK$79 billion. The government held the line at 7,829 points, forcing the speculators to settle at high prices and retreat.

This victory, though hard-won, ultimately saved Hong Kong's financial lifeline—the linked exchange rate system. But it left a lasting scar: the regulators internalized an iron rule—stability above all else. Any factor posing a potential threat to financial stability must be subjected to the strictest scrutiny.

This is Hong Kong's first layer of muscle memory.

If the 1997 crisis was an external shock, the 2008 crisis was a fire in its own backyard. Although the fire started in the US, it was the trust between Hong Kong's ordinary citizens and the elites in Central that ultimately burned.

That year, the collapse of Lehman Brothers across the ocean sent shockwaves like a tsunami toward Hong Kong. Over 40,000 Hong Kong citizens, most of them elderly retirees relying on their pensions, saw their Lehman Brothers-linked mini-bonds become worthless overnight.

These mini-bonds were packaged as low-risk, high-return financial products and sold through banks to the least risk-tolerant ordinary people. This event exposed internal regulatory loopholes and mis-selling practices within Hong Kong's financial system, severely shaking public trust in financial institutions.

This incident directly led to stricter investor protection regulations and more complex sales processes for financial products in Hong Kong. It made regulators almost pathologically cautious about any financial innovation that could trigger systemic risk, especially that which could harm ordinary investors.

This is Hong Kong's second layer of muscle memory.

Hong Kong's financial regulatory system, shaped by these two crises, embarked on a path that极度 emphasizes stability and safety. This path dependency helped Hong Kong successfully weather external shocks over the past two decades. But it also made the system seem格格不入, even水土不服, when facing a completely novel financial technology revolution characterized by disruption and decentralization.

So, what kind of fractured economic reality has this muscle memory, rooted in historical trauma, created in today's Hong Kong?

A Divided Hong Kong: Whose Prosperity? Whose Despair?

Historical trauma has ultimately torn three chasms across Hong Kong's landscape. The city is now in the throes of an all-encompassing economic split.

The first chasm is between finance and the real economy.

While global dealmakers and investment bankers once again focus on Hong Kong, celebrating its return to the top of the global IPO fundraising rankings, Hong Kong's real economy is experiencing a prolonged winter.

According to data from the Official Receiver's Office, winding-up petitions submitted by companies in 2024 reached 589, the highest since the SARS outbreak in 2003. Within a year, over 500 stores closed down quietly, including local time-honored brands like China Resources Vanguard (CR Vanguard), Dah Chong Hong Foods, and Sincere Department Stores, which had accompanied generations of Hong Kongers. The prime locations in Causeway Bay and Tsim Sha Tsui, once places where retail space was fiercely contested, are now lined with shuttered roll-down gates and "For Lease" signs.

The萧条 of the real economy is directly reflected in the job market. Hong Kong's overall unemployment rate hovered around 3% for most of 2025, but the unemployment rate in the retail, accommodation, and food services sectors was far above the average, and the jobless rate for those aged 20 to 29 remained stubbornly high. On one side, recruitment ads in the financial sector are bustling, and traders' bonuses hit new records; on the other, waves of layoffs in the retail sector continue unabated, and the jobs of ordinary citizens are insecure.

Prosperity has never been so concentrated; despair has never been so widespread.

The second chasm is between the elites and the common people.

If the finance-real economy chasm depicts an industry split between ice and fire, the elite-common people chasm reveals a疏离 of hearts and minds. This疏离 is most直观地体现在 in the flow of money and people.

On one hand, global tycoons and mainland elites are voting with their wallets, flooding into Hong Kong.

In 2024, Hong Kong's asset and wealth management business recorded net inflows of HK$705 billion, a historical high. Mainland buyers' total value and number of transactions in Hong Kong's property market surged nearly tenfold, purchasing residential properties worth HK$138 billion in a year. Transactions of ultra-luxury homes worth over HK$100 million were火爆, seemingly completely unaffected by the economic cycle.

On the other hand, ordinary Hong Kong citizens are voting with their feet, flooding into the mainland.

In 2024, Hong Kong residents made 77 million trips northbound, spending nearly HK$55.7 billion on the mainland. From a meal and a milk tea to dental care and beauty treatments, Shenzhen and Zhuhai became the preferred weekend destinations for Hong Kongers.

Deeper population movements are reflected in cross-border marriages, education, and retirement.

According to data from the Census and Statistics Department, the proportion of "Hong Kong women marrying north" (to mainland husbands) soared from 6.1% in 1991 to 40% in 2024; over 30,000 cross-border students travel between Shenzhen and Hong Kong daily; nearly 100,000 Hong Kong elderly have chosen to retire in Guangdong, enjoying lower costs of living and more spacious environments.

While the elites of a city discuss the globalization of asset allocation, its citizens ponder which restaurant in Shenzhen offers the best value for their next meal. One side basks in the afterglow of a monetary empire; the other is mired in a底色 of stagnation.

The third chasm is between assets and innovation.

Hong Kong is never short of money, but the money doesn't seem to flow to where it's most needed.

Hong Kong's R&D intensity—the ratio of R&D expenditure to GDP—has long hovered around 1.13%. This figure is less than half of Singapore's and only a quarter of South Korea's. Even more unsettling is that just across the border, Shenzhen's R&D intensity has long surpassed the 5% threshold.

Although the number of startups in Hong Kong reached 4,694 in 2024, a 10% year-on-year increase, their average size was only 3.8 people, revealing a窘境 of遍地小草 (grass everywhere) but不见大树 (no big trees).

Capital prefers to chase assets with high certainty, like real estate and stocks, rather than high-risk, long-return-cycle technological innovation. The high cost of housing and rent also severely squeezes the生存空间 of startups. In Hong Kong, a young entrepreneur's biggest headache is often not finding a good direction, but affording next month's office rent.

The chasm between finance and the real economy, between elites and common people, and between assets and innovation, together paint a bizarre economic picture of Hong Kong. It resembles Marvel's MODOK, with an abnormally发达 head (finance), while the torso and limbs (real economy, innovation) are gradually萎缩.

So, on such soil, how will the seed of financial innovation take root and sprout? Will it transform this soil, or will it be transformed by it?

Financial Innovation Without Winners

The answer is, it gets transformed by the soil. Financial technology innovation in Hong Kong has been a top-down, strictly controlled movement of reform from the very beginning.

Here, you cannot both tame the fire and expect it to illuminate the darkness.

The first battlefield of this reform movement was payments.

Once upon a time, the tiny Octopus card was an innovation Hong Kong was proud of. But when the mobile payment wave swept the globe, Octopus was slow to react, giving mainland payment giants and local innovators huge room for imagination.

However, what ultimately unified the battlefield were neither WeChat Pay nor Alipay, nor any ambitious startup, but two products with strong "official" and "establishment" colors: HSBC's PayMe and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority-led Faster Payment System (FPS).

PayMe, born with a silver spoon, is backed by Hong Kong's largest note-issuing bank, HSBC, possessing a vast existing customer base and unparalleled brand trust. FPS is a cross-bank payment infrastructure built by the regulator itself.

Their victory is less a triumph of product and more a triumph of "order." This so-called payment war was never a fair fight from the start. Traditional financial giants and regulators, by proactively launching改良型 products, successfully kept other innovators at bay, consolidating their own positions.

If innovation in payments was corralled from the beginning, virtual banks were entrusted with the厚望 of being "catalysts" (鲶鱼 - catfish).

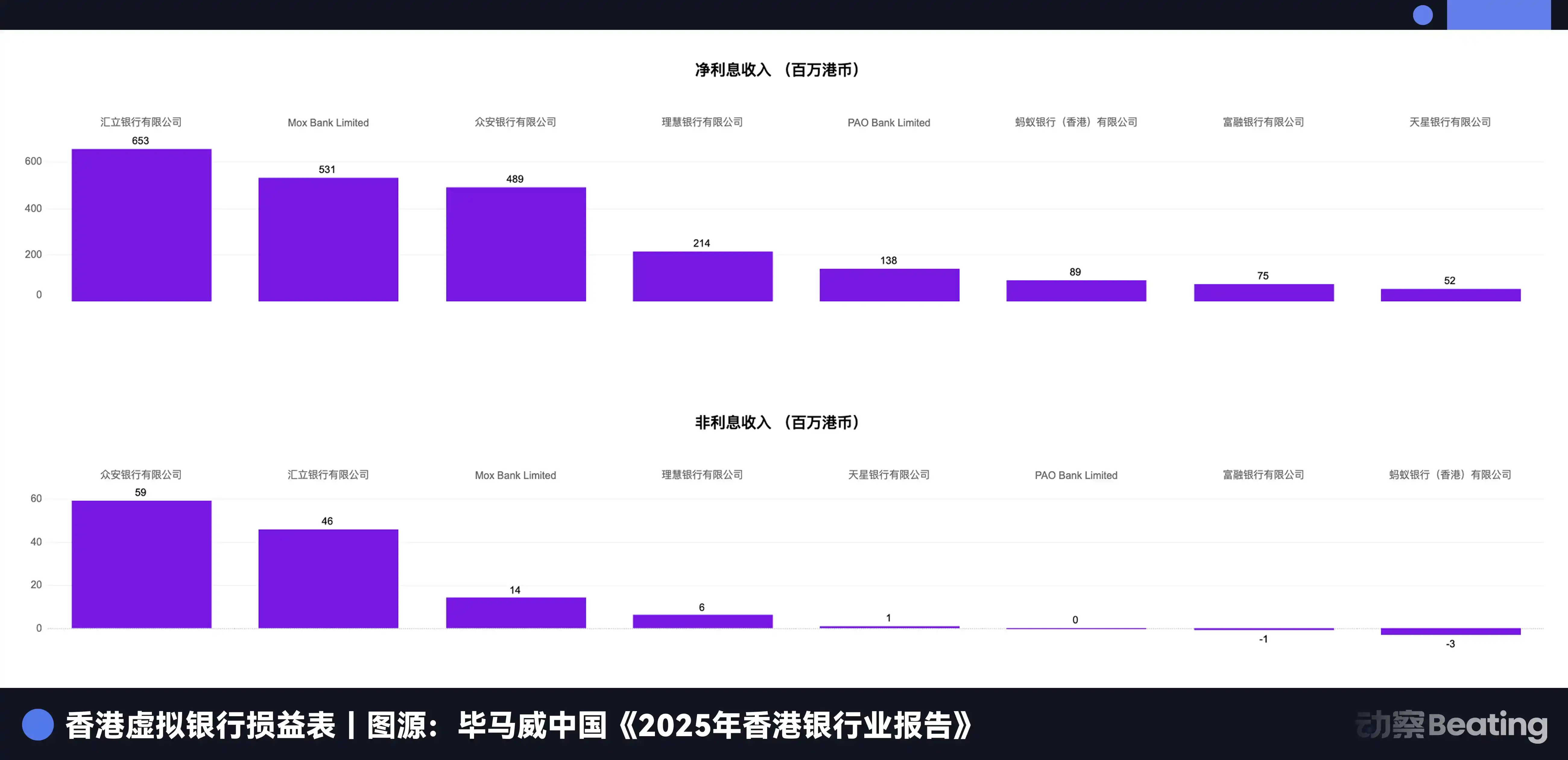

In 2019, the HKMA issued 8 virtual bank licenses in one go, hoping these catfish would stir the stagnant waters of traditional banking. However, five years on, the 8 virtual banks have collectively burned through over HK$10 billion, only to gain less than 0.3% market share.

It wasn't until the first half of 2025 that ZA Bank, WeLab Bank, and livi Bank recorded their first profits, but the combined losses of all eight still amounted to HK$610 million. The vast majority of Hong Kong citizens still use traditional banks as their primary accounts; virtual banks are more like electronic wallets used occasionally for transfers or grabbing promotional offers.

They failed to颠覆 anything; instead, they themselves fell into a生存困境. The few virtual banks that achieved profitability first did so not through disruptive product or service innovation, but by finding grey areas traditional banks were unwilling to touch, such as providing account services for Web3 companies.

This is less a victory for the "catfish" and more a compromise of being招安 (co-opted/absorbed into the establishment). They ultimately did not become challengers but turned into patches for the existing financial system.

A more interesting phenomenon occurred in wealth tech and insurtech.

These two sectors were listed by the HKMA as the most promising fintech tracks worthy of support because they perfectly align with Hong Kong's core interest: consolidating its position as a global asset management center. Wealth tech makes asset management for high-net-worth clients more convenient; insurtech makes selling insurance products more efficient. They are safe innovations that serve the established order, tools that add flowers to brocade (锦上添花).

Thus, we see the "selective prosperity" of Hong Kong's fintech. On one side is the spectacle of asset under management breaking through HK$35 trillion; on the other, virtual banks struggle within a 0.3% market share. Fintech serving the wealthy gets the green light, while fintech attempting to serve the masses and change the landscape hits walls everywhere.

From payments and banking to wealth management, Hong Kong's fintech innovation shows a clear pattern: embrace改良 (reform), resist革新 (revolution).

This ultimately evolved into a war with no winners. Traditional giants, while protecting their moats, may have lost the drive for more radical, future-oriented innovation; and those passionate innovators, after paying a heavy price, ultimately failed to truly change the market's rules of the game.

If even in relatively mature fintech areas like payments and banking, Hong Kong chose such a conservative path of招安, then what choice will it make when facing a truly wild, unpredictable, decentralization-souled revolution like Web3?

Hong Kong's Web3 Embarrassment

If Hong Kong's approach to fintech is招安 (co-option), its approach to Web3 is another kind of trade-off: embrace its form, reject its spirit.

In late 2022, Hong Kong loudly proclaimed its ambition to become a global virtual asset center. Policy statements flew thick and fast, from retail investor access to stablecoin regulatory sandboxes. Hong Kong posed as embracing the future. However, over two years later, what arrived was a classic Hong Kong-style embarrassment.

In April 2024, when Hong Kong beat the US to launch Asia's first batch of spot virtual asset ETFs, the market was euphoric. However, the honeymoon period was as brief as a summer shower. By the end of 2025, the total assets under management (AUM) of Hong Kong's 6 virtual asset ETFs were merely US$529 million, compared to over US$45.7 billion for similar US products—a difference of more than 80 times.

Same ETF, same asset, but born south of the Huai River it's an orange (flourishes), born north (Hong Kong is north) it's a trifoliate orange (sour and inedible).

A deeper embarrassment lies hidden under the tight箍咒 (headband spell/tight constraints) of compliance. Hong Kong has set some of the world's strictest regulatory standards for virtual asset trading platforms. While this杜绝 (prevents) risks like the FTX collapse, it also brings extremely high compliance costs.

According to industry insiders, a licensed virtual asset trading platform in Hong Kong has monthly operating costs as high as US$10 million, with 30% to 40% spent on compliance, legal, and auditing. This is bearable for giants, but for the vast majority of small and medium-sized startup teams, it's an insurmountable chasm.

The JPEX incident in 2023 pushed this embarrassment to the extreme. This unlicensed platform used疯狂 marketing online and offline, luring大量普通市民 with promises of "zero risk, high returns," ultimately blowing up with involved funds高达 HK$1.6 billion.

The恶劣 impact of the JPEX incident was that it created a劣币驱逐良币 (bad money drives out good) effect at the social level, generating extreme distrust among the general public toward the entire Web3 industry and further strengthening the regulators' resolve to严防死守 (guard rigidly against all risks).

Thus, a paradoxical cycle formed. The more absolute safety is pursued, the higher the regulatory cost; the higher the regulatory cost, the harder it is for licensed institutions to compete with unregulated "wild platforms"; the blow-up of "wild platforms" further reinforces the need to pursue absolute safety.

Hong Kong tried to build an impregnable safe house for Web3, only to find that once the house was built, the participants of innovation either chose to build new stoves outside or suffocated inside due to繁琐 rules.

At this point, Hong Kong's true attitude towards Web3 is clear. It welcomes cryptocurrency as an alternative asset to be incorporated into the existing financial system—a financial product that can be valued, traded, and managed. But it rejects, or fears, cryptocurrency as a tool of revolution—the Web3 with decentralization, censorship resistance, and disruption of intermediaries at its core spirit.

The former can add a new板块 (sector) to Hong Kong's asset management map; the latter could shake the very foundation of that map.

This is the most fundamental conflict between "yesterday's rules" and "tomorrow's innovation." Hong Kong uses the logic of managing stocks, bonds, and real estate to manage a new species. The result: it rejected the innovation itself, leaving behind a policy独角戏 (one-man show) with no audience applause.

The Turning of the Giant Ship

Looking back at Hong Kong's fintech journey is like observing the difficult turning of a giant ship.

This ship named Hong Kong was undoubtedly one of the world's most successful vessels over the past half-century. However, the financial revolution did not bring a storm, but a drop in sea level and the rise of new continents. It revealed countless narrow, winding, reef-strewn new channels in what was once a deep, unfathomable ocean.

In these new channels, the giant ship's advantages become its most fatal disadvantages. It is too large to turn around in narrow passages; it is too heavy to move in shallow waters; its navigation system is completely失灵 (useless) in the全新的水文环境 (entirely new hydrological environment).

In economics, there is a concept called the "curse of the successful." It refers to how past great success creates a powerful path dependency and mindset that prevents adaptation to new paradigms, ultimately causing one to be反噬 (consumed/defeated) by one's own past success. This is perhaps the most accurate summary of Hong Kong's current predicament.

Hong Kong's迷失 (being lost) is not about what it did wrong, but about它把过去做对的事情, 在错误的时间里, 又重复了一遍 (it repeating the things it did right in the past, but at the wrong time). It tried to use the method of building fortresses to embrace a flowing feast; it tried to use the skills of reforming the old system to embrace an innovation aimed at starting over from scratch.

Today, this giant ship is anchored in the middle of Victoria Harbour, its engines still roaring, but its captain and crew are deeply迷茫 (lost and confused). On the distant horizon,无数轻巧的快艇 (countless nimble speedboats) are speeding along the new channels, leaving it far behind.

History has never granted any city permanent exemption. When yesterday's glory becomes today's shackles, only the courage to break those shackles can win tomorrow.