Author: Yash Chandak

Original Title: Stop Saying ‘We Need Privacy’

Compiled and Edited by: BitpushNews

If your wallet is public, your life is public. People can stare at your balance, your transactions, your positions, and your entry timing, then casually say it's "just data." This is why "privacy" always returns as an enduring narrative.

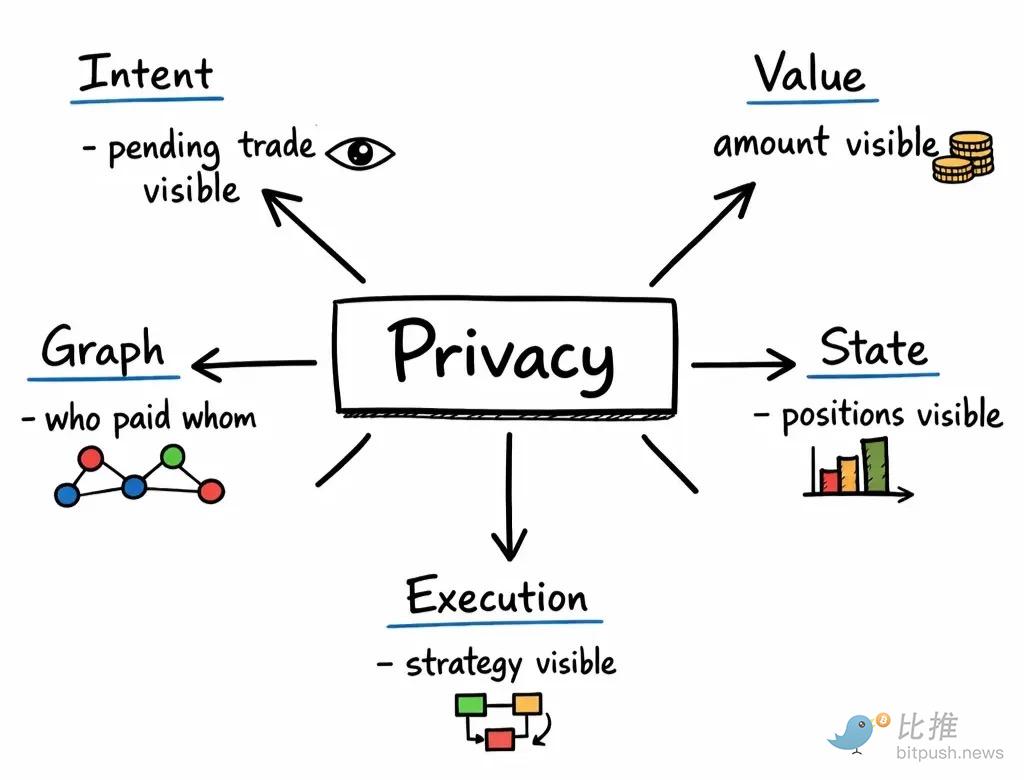

The problem is, "privacy" is not a single feature. It is actually five distinct problems.

This article is written to help you understand what you are actually asking for the next time you tweet "We need privacy."

When people mention privacy, they often refer to completely different things:

-

Intent privacy: Observers should not see your transaction before it is executed.

-

Value privacy: Your salary, net worth, or transaction size should not be easily observable.

-

State privacy: Positions, liquidation thresholds, vault status, and inventory should not be public by default.

-

Execution privacy: Your strategy should not be inferred from which paths you trigger and how you trigger them.

-

Graph privacy: Observers should not be able to map out who you pay, who you donate to, or who you collaborate with.

Many "privacy protocols" only solve one or two of these problems while leaking the others. Most leaks happen at the edges: wallets, Remote Procedure Calls (RPCs, the bridge between wallets and the blockchain), relays, bridges, exchanges, and the predictability of human behavior.

This is a framework to clarify the industry landscape: first identify the surface you want to protect, then find the tool that protects that surface.

Intent Privacy

On many chains, transactions do not go directly from your wallet into a block. Instead, they first sit in a public waiting room called the "mempool," where pending transactions are visible before being included. If you can see a pending swap, you can react to it. This creates opportunities for Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) bots. These bots are high-speed automated systems that monitor the blockchain mempool to find and exploit profitable trading opportunities, such as arbitrage, liquidations, and sandwich attacks.

For example, a bot can discover your swap request, buy before you, causing the price to move against you, and then sell immediately after you to profit from the差价. You get your trade done, but at a worse price.

Intent privacy addresses this specific ~12-second window. The goal is to hide transaction details until observers来不及 react.

Private Transaction Delivery

The most practical way to ensure transaction delivery privacy is to change its path. Your wallet still creates a normal signed transaction. The difference is where it is sent. Instead of being broadcast to the public mempool, the transaction is submitted to a private endpoint, which forwards it to block builders. These builders assemble candidate blocks by ordering transactions, and finally, a validator publishes one of the blocks.

This is what systems like Flashbots Protect offer: a route that keeps your transaction away from the public mempool before it enters a block.

Flashbots is also researching a concept called SUAVE (Single Unified Auction for Value Expression), which frames the problem as "order flow itself is a system." The idea is to collect user intents in a private environment, run auctions to determine who executes them, and then settle the results on Ethereum and other chains.

While still evolving, this approach sets a clear direction: privacy should be applied before a transaction touches the public mempool.

The reason this works is also its trade-off. It works because public bots never get to see it early. The trade-off is that the private管道 and builders *do* see it early. You are just narrowing the audience, not eliminating提前 visibility entirely.

Encrypted Mempool

Encrypted mempools aim to provide stronger privacy, ensuring that no one (including builders) can see the transaction before it is included in a block.

The network sees not a readable transaction, but an encrypted binary large object (blob). Observers can tell that *something* was submitted, but not what.

Decryption only happens after orders are locked in. A common design uses threshold decryption, where decryption authority is split among a committee (Shutter Network calls them Keypers). Each committee member holds a shard. When it's time to reveal the content, enough shards are published to reconstruct the decryption key, allowing the transaction to execute.

This approach removes the "private管道 sees everything early" problem, but it introduces new assumptions: the committee must be online and must not collude.

Intent privacy ends at block publication. Unless you combine it with on-chain value, state, or execution privacy, the information contained in the block will still be exposed as usual.

Value Privacy

Value privacy answers a simple question: Can I transfer money without letting the world see how much I sent?

On normal public chains, the answer is no. Every transaction publishes the amount directly, which is how everyone verifies balances.

"Shielded systems" change this by separating two things:

-

The amount (kept private)

-

The proof of遵守 rules (kept public)

Under the hood, the system stores your funds as private records. You can think of them as encrypted receipts. Each receipt represents a certain amount, but only the owner knows how much is inside.

When you spend:

-

You prove you own a valid receipt.

-

You prove you haven't spent it before.

-

You create new receipts for the recipient (and give yourself change).

-

You publish a proof that the total amount going out equals the total amount coming in.

The chain is responsible for checking this proof. If the proof is valid, the transaction is accepted, but the hidden amounts remain unknown to the outside world. This is the core design behind Zcash's shielded transactions and a classic production example of value privacy. Penumbra uses the same general concept in its multi-asset shielded pool, where all value resides within the private pool, and transfers happen via proofs rather than visible amounts.

But this privacy has limitations. Even if the math is perfect, privacy can still fail. Leaks often stem from user behavior:

-

If you deposit a very specific amount and later withdraw the exact same amount, observers can guess it's the same person.

-

If you move in and out of the private pool within minutes, the timing becomes a clue.

-

If only a few people are using the private pool, the anonymity set is small.

-

If you immediately transfer funds to a known exchange account, you reconnect the identity.

So, value privacy hides the numbers inside the system, but it doesn't automatically hide the behavioral patterns around that system.

Graph Privacy

Graph privacy focuses on relationships. Even if you hide the amount, the public ledger can still reveal patterns: who you send to, who you receive from, how often, and the amounts. Over time, this network map can be more revealing than balances.

Most graph privacy methods fall into two categories:

The first is Pooled unlinkability. This is the idea of "mixing." A large number of users send funds to the same pool, which are later withdrawn in a way that makes it impossible to link specific withdrawals to specific deposits on the public level. The chain still shows deposits and withdrawals.

Privacy comes from ambiguity. Observers can see deposits and withdrawals, but cannot reliably match them. Any single withdrawal could logically belong to many participants. This is the core mechanism of mixer systems like Tornado Cash. The larger the pool, the less certain observers are about any single link.

If the pool is busy and many people deposit the same amount, you disappear into the crowd. If the pool is small, the crowd crumbles, and the graph reasserts itself through timing and amounts.

Another way to break the graph is to stop reusing the same receiving address.

If every payment goes to a public address, your receiving history becomes a permanent public feed. Anyone can cluster these payments and assume they belong to the same person.

Stealth addresses can change this pattern. Each payment is no longer sent to a single visible destination, but lands on a new address that appears unrelated to the previous one. The sender generates a one-time address for that payment, which only the intended recipient can access. To an external observer, it looks like funds are going to unrelated addresses.

This does not hide the amount or the sender. It solves a narrower problem by preventing outsiders from linking all receipts to the same identity. ERC-5564 standardizes this pattern for Ethereum. It doesn't hide the sender or amount, but it makes "all payments to Alice" no longer obvious.

Graph privacy still leaks through behavior. If you withdraw from the pool and immediately bridge to the same place every time, you create a new linking point. If you cash out and immediately interact with a KYC exchange, identity is instantly recovered. If you maintain the same timing habits, the graph becomes guessable. These systems break direct links, but they don't erase your footsteps.

State Privacy

State privacy aims to solve problems specific to DeFi. Your balances, positions, liquidation thresholds, vault composition, and inventory should not be readable by anyone with a block explorer.

This is important because "public state" becomes strategy leakage. If your positions are visible, other participants can predict your actions, when you will be liquidated, and what you might do next. Worse, they can target you. A wallet with a visible liquidation line is basically a public scoreboard.

So what does state privacy change under the hood?

On a normal chain, state is something everyone agrees on and can read. Lending protocols map addresses to position details. Vaults map addresses to shares and debt. This is what indexers and bots scrape.

Private state systems stop writing these details in plain text. They replace "public state indexed by your address" with "private state represented by hidden records," and force state updates to be accompanied by proofs that the update follows the rules.

Here's the simplest way to understand it:

-

You still perform actions like "deposit collateral," "borrow," "rebalance," or "swap."

-

The chain must still enforce constraints like "your borrowing cannot exceed what your collateral allows," "you cannot create value out of thin air," and "you cannot double-spend the same private balance."

-

But the chain enforces these constraints by verifying proofs, not by reading your positions.

This is why state privacy and Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZK proofs) are often inseparable. You need something to declare "this update is valid" while keeping the underlying numbers private.

A concrete example is Aztec. Its design centers on client-side private execution, with the network responsible for verifying proofs and commitments. This allows positions to exist without being stored as readable tables on-chain. You can perform DeFi-like operations, and the public chain only sees state transitions verified by proofs, not your raw positions.

Where does state privacy leak? Still mostly at the edges.

If you have a private position but regularly exit to a public Decentralized Exchange (DEX), the size and timing of these exits can reconstruct your behavior. If you move in and out of bridges in predictable patterns, you create links. If you rely on public keepers for liquidation, your "private" position still needs some interface with the outside world, and that interface might leak information.

Furthermore, state privacy makes composability difficult. Public DeFi works like Lego because everyone can read everything. Private DeFi must answer: "How do two contracts interact when neither can see the other's internals?" The more complex the composition, the more careful the design needs to be.

State privacy is where privacy升级 from "hiding a single transfer" to "hiding an ongoing financial posture," which is why it's harder to achieve, more useful, but also more prone to crumbling at the boundaries.

Execution Privacy

This category of privacy goes a level deeper. It hides not only balances or positions but also *how* the computation happens. This is crucial for auctions, matching, solver logic, liquidation strategies, private order types, and any scenario where the strategy would be exploited once visible.

There are two common approaches:

-

One uses Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs). The contract executes inside a hardware enclave, inputs are decrypted inside the enclave, outputs are encrypted, and its operation is verified via attestation. Secret Network and Oasis Sapphire are examples using this approach for private execution with lower proof overhead. The trade-off is trust in the hardware and the risk of side-channel attacks.

-

The other approach uses ZK proofs for private execution. The system produces evidence that the program ran correctly without revealing the private inputs that drove the execution. This approach is conceptually pure but often has high tooling and performance demands and is often rolled out in limited scope before becoming widespread.

Execution privacy is weak in the same areas as other privacy types: timing, boundary interactions, and the access layer.

RPC: Where Privacy Breaks

Even if your on-chain privacy is perfect, if your wallet uses Infura or Alchemy, that RPC provider can see your IP address, the addresses you control (because you query their balances), which contracts you interact with, and your timing patterns.

In 2022, ConsenSys publicly acknowledged that MetaMask's default RPC (Infura) collects IP addresses and wallet addresses. This is why protocol privacy often fails in practice: the access layer leaks everything before the cryptography has a chance to work.

So, privacy is shaped by context. Different contexts shape privacy design in different ways.

Trading primarily needs intent privacy. Payments need value privacy and graph privacy on the recipient's side. DeFi craves state privacy. Bridges add correlation points. Institutions want confidentiality while having a path for verification and accountability.

Therefore, the question "Which privacy model will win?" is often the wrong question.

A more accurate question is: Which surface are you protecting? What assumptions are you making? And where else will information leak when users touch the real world?

Twitter:https://twitter.com/BitpushNewsCN

Bitpush TG Discussion Group:https://t.me/B极狐itPushCommunity

Bitpush TG Subscription: https://t.me/bitpush