Original | Odaily Planet Daily (@OdailyChina)

Author | DingDang (@XiaMiPP)

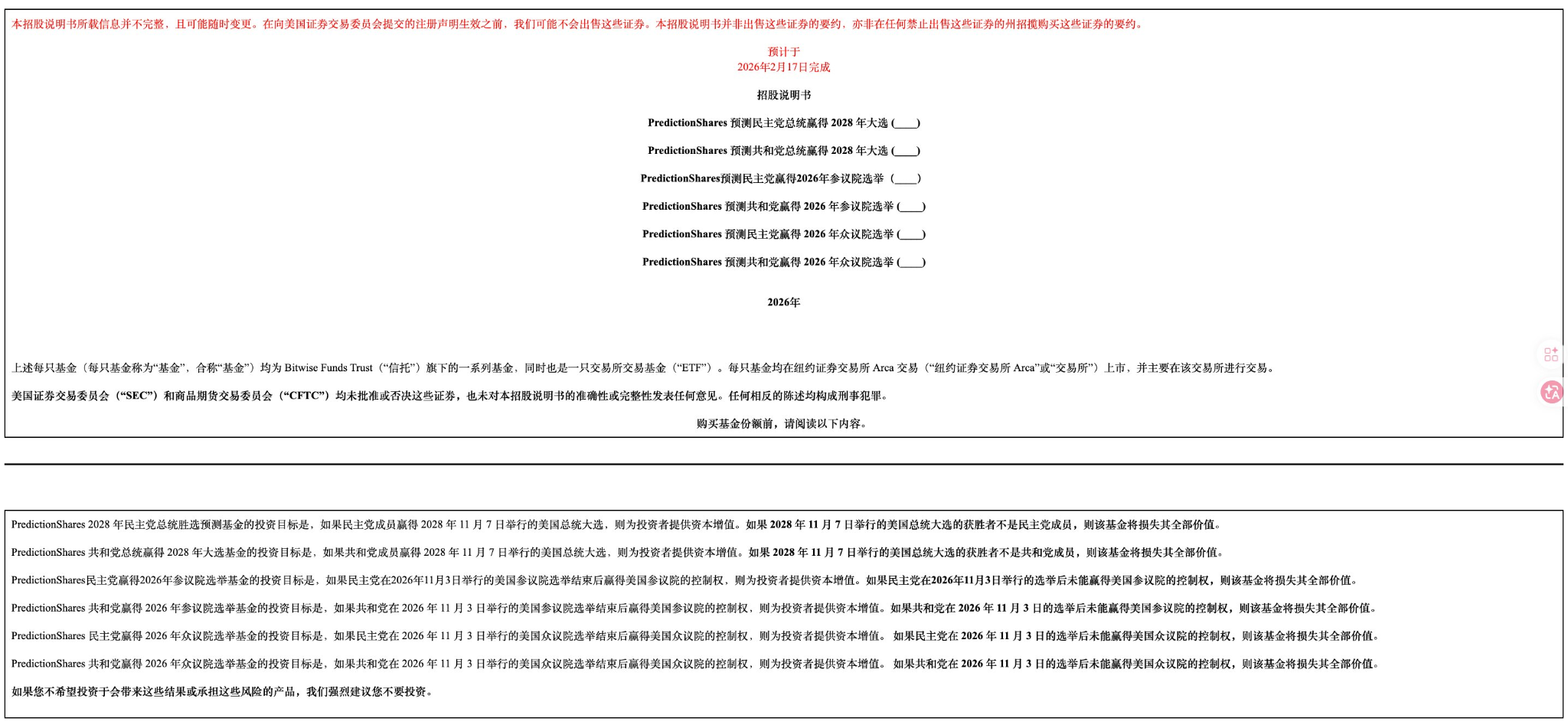

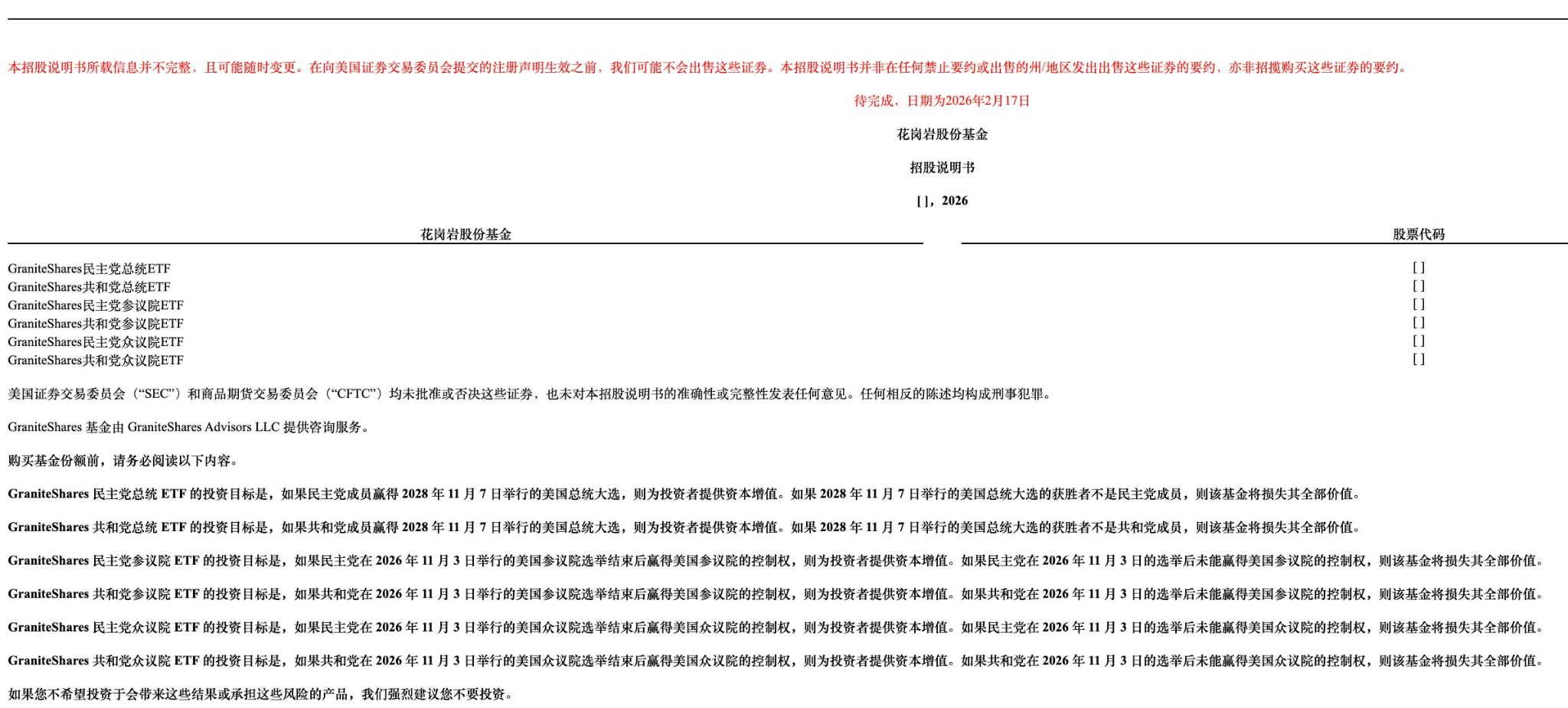

Recently, ETF issuers Bitwise Asset Management and GraniteShares have filed applications with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for prediction market ETFs. Among them, Bitwise submitted six products under the "PredictionShares" brand, and GraniteShares quickly followed with a similarly structured proposal. A bit earlier, on February 13th, Roundhill Investments also filed documents for a similar type of product.

The core of these ETFs is tracking the outcomes of U.S. political elections. They attempt to package the "probability of outcomes" of U.S. political elections into a financial product that can be traded directly in traditional securities accounts. Specifically, the underlying focus is on the 2028 presidential election (whether the Democrat or Republican wins) and which party will control the Senate and House of Representatives in the 2026 midterm elections.

In other words, investors in the future might no longer need to go to the crypto world's Polymarket or register with the CFTC-regulated Kalshi; they could simply open their Robinhood or Fidelity account and place a bet on "who will win the White House" just like buying a stock.

Screenshot from @jason_chen998

What does this leap forward signify?

Why Do Prediction Markets Always Seem "One Step Ahead"?

The "foresight" of prediction markets regarding political events is hardly news anymore.

A prediction market is essentially a group of people using real money to express judgments. Participants buy and sell "Yes/No" contracts to express their confidence in an event occurring. The prices of these contracts fluctuate between $0 and $1, representing the market's consensus on probability. For example, if you believe a candidate has a 70% chance of winning, you might buy a "Yes" contract for $0.70. If the event happens, the contract's value rises to $1; otherwise, it becomes worthless.

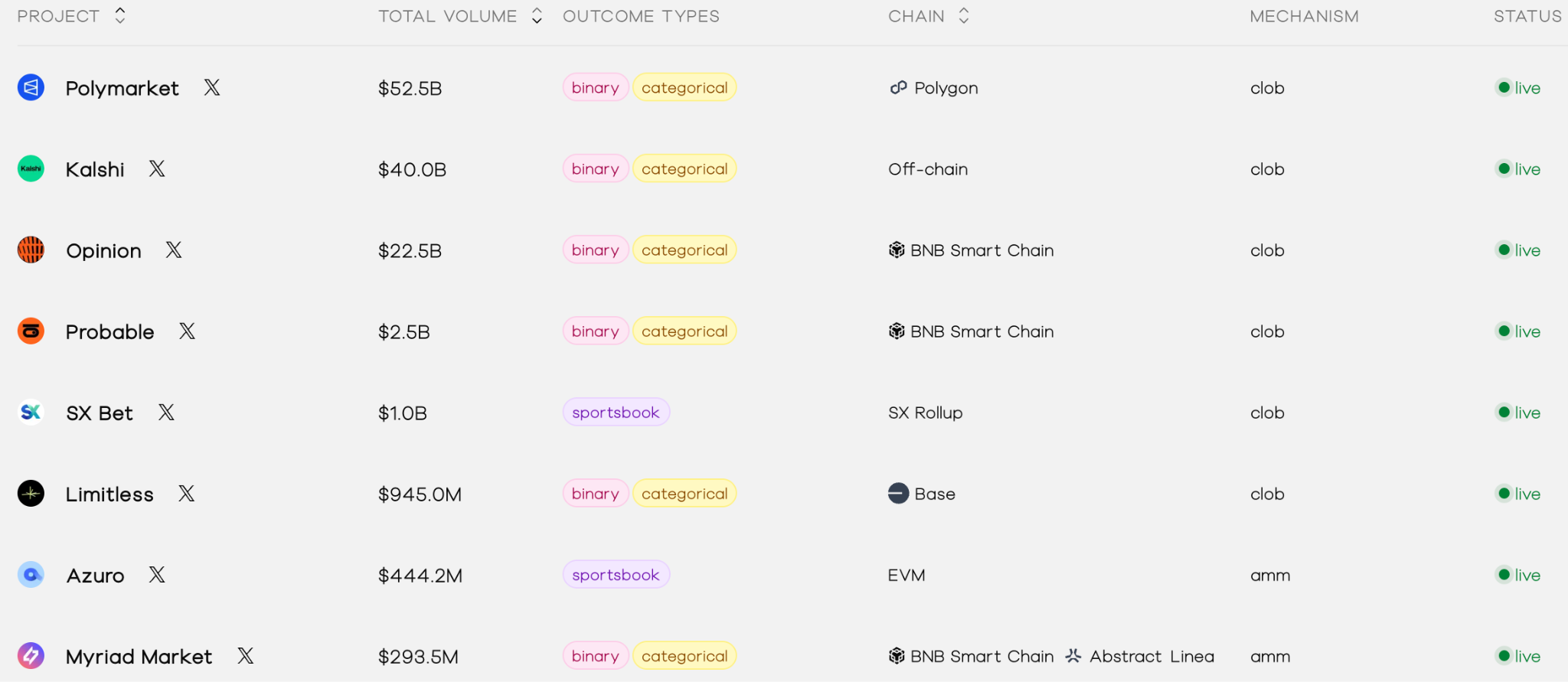

This is a form of crowd judgment weighted by capital. Unlike mere verbal expression, participants must bear the consequences of profit and loss for their judgments. The 2024 U.S. election was a concentrated example. At that time, trading volumes on Polymarket and Kalshi surged rapidly, with political contracts becoming the absolute mainstay. Before election day, the cumulative trading volume on Polymarket for the single market "2024 Presidential Election Winner" was approximately $3.7 billion. Kalshi, a later entrant, won a key lawsuit against the CFTC in September 2024, allowing it to legally offer election-related contracts. By November, its monthly trading volume reached $127 million, with about 89% coming from politics and election markets.

More noteworthy is the signal the data itself conveyed. Weeks before the 2024 election, the probability of a Trump victory on Polymarket stabilized above 60%, while mainstream polls showed a tight race, sometimes even with Harris slightly ahead. The result? The prediction market seemed to "read" the election situation early.

This doesn't mean prediction markets are "magically accurate," but across multiple election cycles, they have indeed demonstrated a strong ability to aggregate information. Research has found that, with sufficient liquidity and broad participation, the statistical performance of prediction markets often surpasses that of traditional poll samples. The older platform PredictIt has also been repeatedly regarded as an effective information aggregator. In contrast, traditional polls are susceptible to factors like sample bias and response bias.

The root of the difference lies in the incentive structure: polls express attitudes, prediction markets entail bearing consequences. The former has no cost, the latter has clear profits and losses. This structural difference determines the different ways information is processed.

Although prediction markets cooled down significantly after the election—Polymarket's daily trading volume plummeted by about 84% after the results were announced—the number of prediction market projects grew rapidly entering 2025. Now, in 2026, data from predictionindex.xyz shows there are as many as 137 prediction market projects, with the leading player, Polymarket, having a total trading volume exceeding $50 billion and a monthly trading volume of $8 billion.

From a fringe experiment to a mainstream sector, prediction markets are a far cry from what they once were. Now, imagine if participation could be made easy through ETFs; this collective intelligence could influence public perception of political events even more widely.

How ETFs Package Prediction Markets

So, how are these ETFs bringing the玩法 (gameplay) of prediction markets to Wall Street?

What these issuers are doing is essentially translating the contract prices of prediction markets into a product structure understandable by the securities market. Dressed in the cloak of an ETF, it allows you to buy and sell through a正规 (formal) brokerage account, but you're still betting on the outcome of a political event.

Taking the six ETFs filed by Bitwise as an example, four directly target the 2028 presidential election (Democrat/Republican win), and the remaining two correspond to control of the Senate and House in the 2026 midterm elections. The structures from GraniteShares and Roundhill are largely similar. Simply put, these ETFs directly map the price performance of those binary event contracts on Kalshi or Polymarket into tradable ETF shares.

Mechanically, the share price of these ETFs will fluctuate between $0 and $1, reflecting the market's real-time consensus on the event's likelihood. The funds will invest at least 80% of their assets in derivatives linked to these political events, such as contracts obtained from CFTC-approved exchanges like Kalshi, or synthetic swaps to mimic the performance. The buying process is the same as buying a stock: through brokerage accounts like Robinhood or Fidelity, with expected expense ratios between 0.5% and 1%, and the trading venue being NYSE Arca.

At settlement, if the event occurs (e.g., Democrat wins the presidential election), the corresponding "Yes" ETF's value approaches $1; otherwise, it approaches $0. Bitwise's plan is for the fund to liquidate and terminate shortly after the event outcome is determined, distributing the remaining assets proportionally to holders; some products from GraniteShares and Roundhill are more "flexible," potentially allowing a "roll" into the next election cycle.

Compared to the Bitcoin ETFs we are familiar with, there is a clear distinction here. Bitcoin ETFs like BlackRock's IBIT track the price of Bitcoin, with unlimited upside or downside potential, suitable as part of an asset allocation. Prediction market ETFs, however, lean more towards binary probability bets, with a cap fixed at $1, similar to buying insurance or options—winner takes all, loser loses everything.

The question is, when probability becomes a tradable asset, is it still merely an information aggregation mechanism?

Mainstreaming, or Gamblification?

If these ETFs are approved, prediction markets will truly enter the mainstream financial view.

Currently, political prediction markets are still concentrated among crypto users or professional traders. Once ETFs go live, the participation barrier for institutional capital and traditional investors will be significantly lowered. Companies might use them to hedge against policy change risks, and portfolio managers might see them as macro risk management tools. Liquidity will be amplified, and price signals might become sharper.

But the problems on the other side are equally obvious. The 2024 election already proved that prediction market prices are cited by media, amplified on social platforms, and even influence public sentiment. When probability is packaged as "market consensus," it can easily be interpreted as an objective trend. If the scale of capital expands further, could there be deliberate attempts to manipulate prices to influence public opinion? PredictIt was embroiled in legal disputes in its early days due to compliance issues; such concerns are not unfounded.

Regulation remains the biggest uncertainty. The SEC might worry that this is essentially the "gamblification" of finance, increasing the risk of manipulation or moral hazard. The approval process might come with conditions, such as trading limits or additional disclosures. Currently, the CFTC has allowed Kalshi to trade election futures, which is a positive signal, but the SEC's stance remains unclear.

Conclusion

From crypto-native markets to Wall Street ETFs, prediction markets are undergoing an identity transformation. However, before the regulatory framework is clear, the moves by issuers seem more like a probe. They are testing regulatory boundaries and also testing the market's acceptance of "probability as an asset."