Original Author: shaunda devens

Original Compilation: Saoirse, Foresight News

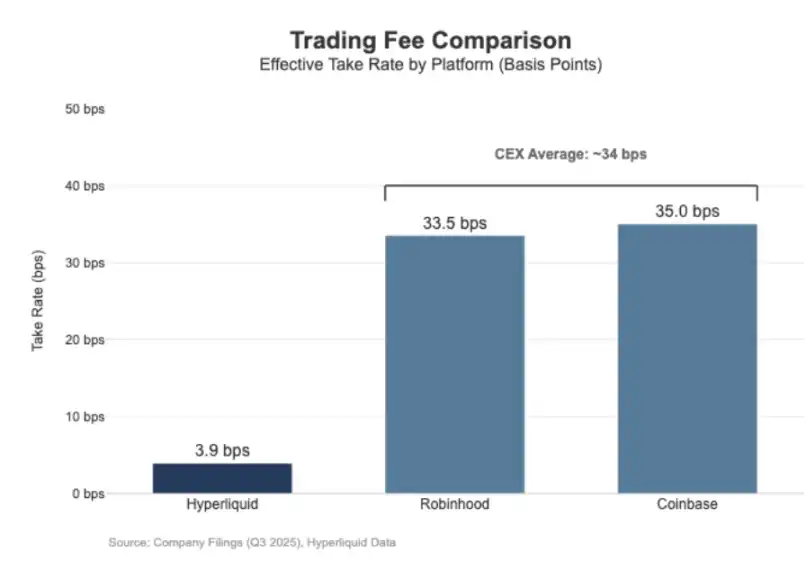

Hyperliquid's perpetual contract clearing volume has reached Nasdaq levels, yet its economic benefits do not match. Over the past 30 days, the platform cleared perpetual contracts with a notional value of $205.6 billion (annualized to $617 billion on a quarterly basis), but generated only $80.3 million in fee revenue, representing a fee rate of approximately 3.9 basis points.

Its profit model resembles that of a "wholesale trading venue."

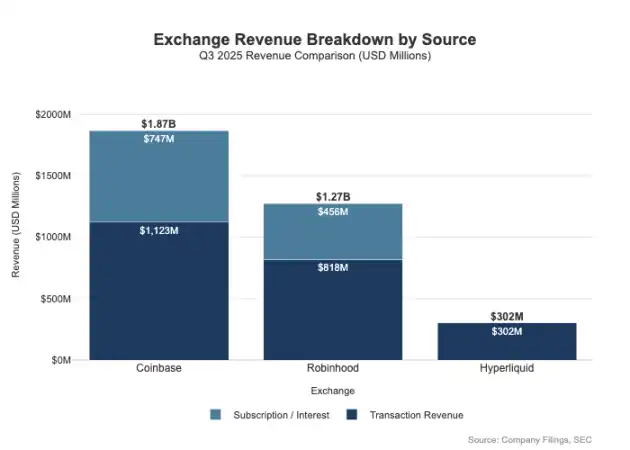

In comparison, Coinbase reported a trading volume of $295 billion in Q3 2025, with trading revenue reaching $1.046 billion, implying a fee rate of 35.5 basis points. Robinhood's cryptocurrency business, on the other hand, demonstrates a similar "retail profit model": $80 billion in cryptocurrency notional trading volume generated $268 million in cryptocurrency trading revenue, implying a fee rate of 33.5 basis points; meanwhile, the platform's stock notional trading volume in Q3 2025 was $647 billion.

The gap is not only in fee rates—retail platforms have more diverse profit channels. In Q3 2025, Robinhood's transaction-related revenue was $730 million, in addition to $456 million in net interest income and $88 million in other revenue (primarily from Gold subscription services). In contrast, Hyperliquid still relies heavily on trading fees, and at the protocol level, its fee rate structurally remains in the single-digit basis points range.

This difference is essentially due to "positioning": Coinbase and Robinhood are "broker/distribution businesses" that profit through balance sheets and subscription services; whereas Hyperliquid is closer to the "exchange level." In traditional market structures, profit pools are distributed across these two levels.

The Divide Between Broker-Dealer and Exchange Models

The core difference in traditional finance (TradFi) lies in the separation of the "distribution end" and the "market end." Retail platforms like Robinhood and Coinbase operate at the "distribution layer," occupying high-margin areas; exchanges like Nasdaq operate at the "market layer"—where pricing power is structurally constrained, and competition in trade execution tends toward a "commoditized economic model" (i.e., profit margins are significantly compressed).

1. Broker-Dealer = Distribution + Customer Balance Sheet

Broker-dealers control customer relationships. Most users do not interact directly with Nasdaq but access the market through brokers: brokers handle account opening, asset custody, margin/risk management, customer support, and tax documentation, then route orders to specific trading venues. This "customer relationship ownership" creates profit opportunities beyond trading:

- Balance-related: cash sweep spreads, margin lending interest, securities lending income;

- Service packaging: subscription services, bundled products, card services/advisory services;

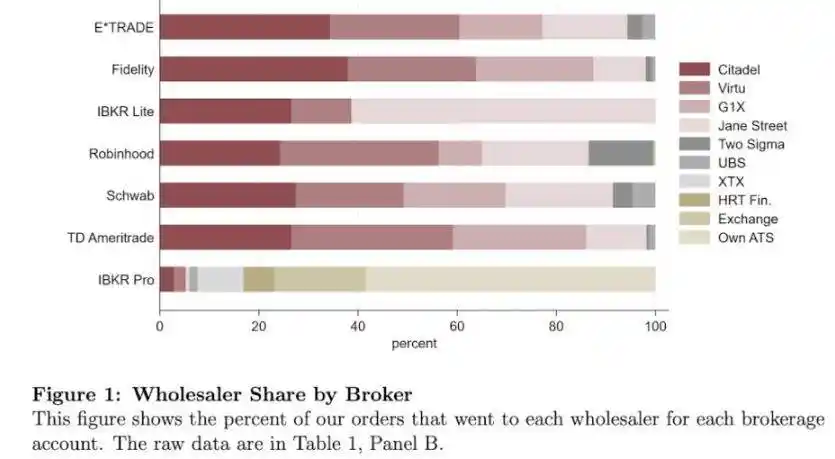

- Order routing economics: brokers control trading flow and can embed payment sharing or revenue-sharing mechanisms in the routing chain.

This is why brokers can profit more than trading venues: profit pools are concentrated in the "distribution end" and "balance end."

2. Exchange = Order Matching + Rule System + Infrastructure, Fee Rates Capped

Exchanges operate trading venues, with core functions including order matching, setting market rules, ensuring deterministic execution, and providing trading connectivity. Their profit sources include:

- Trading fees (in highly liquid products, fees are continuously compressed due to competition);

- Rebates/liquidity incentive programs (to attract liquidity, most public fees often need to be rebated to market makers);

- Market data services, trading connectivity/server hosting services;

- Listing services and index licensing fees.

Robinhood's order routing model clearly illustrates this architecture: the broker (Robinhood Securities) controls users and routes orders to third-party market centers, with revenue shared across the routing chain. The "distribution layer" is the high-margin环节—it controls user acquisition and develops diverse profit channels around trade execution (such as payment for order flow, financing business, securities lending, subscription services).

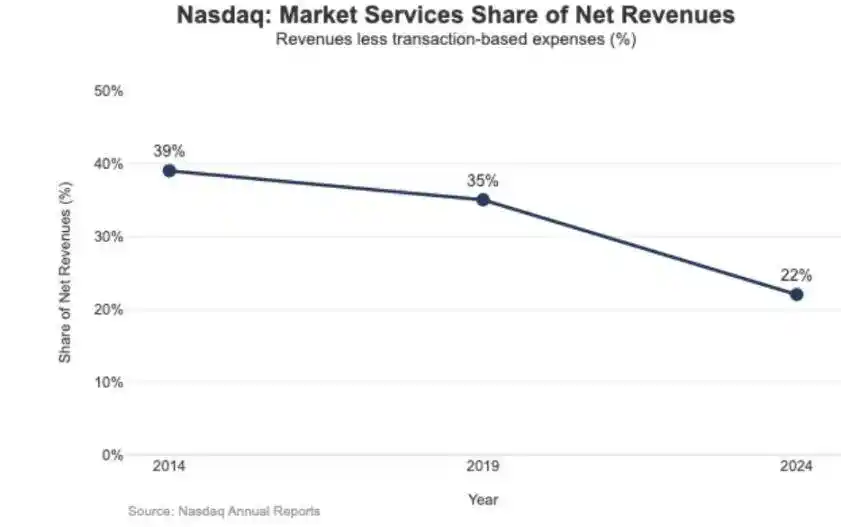

Nasdaq belongs to the "low-margin layer": its core products are "commoditized trade execution" and "order queue access rights," with pricing power mechanically constrained by three factors—the need to rebate fees to market makers to attract liquidity, regulatory caps on access fees, and high elasticity in order routing (users can easily switch to other platforms).

Nasdaq's disclosed data shows that the "implied net cash earnings" per share for its equity business are only at the $0.001 per share (i.e., one-tenth of a cent per share) level.

The strategic impact of low margins is also reflected in Nasdaq's revenue structure: in 2024, "Market Services" revenue was $1.02 billion, accounting for only 22% of total revenue of $4.649 billion; this proportion was 39.4% in 2014 and 35% in 2019—this trend indicates that Nasdaq is gradually shifting from "reliance on market trading execution business" to "more sustainable software/data business."

Hyperliquid Positioned at the "Market Layer"

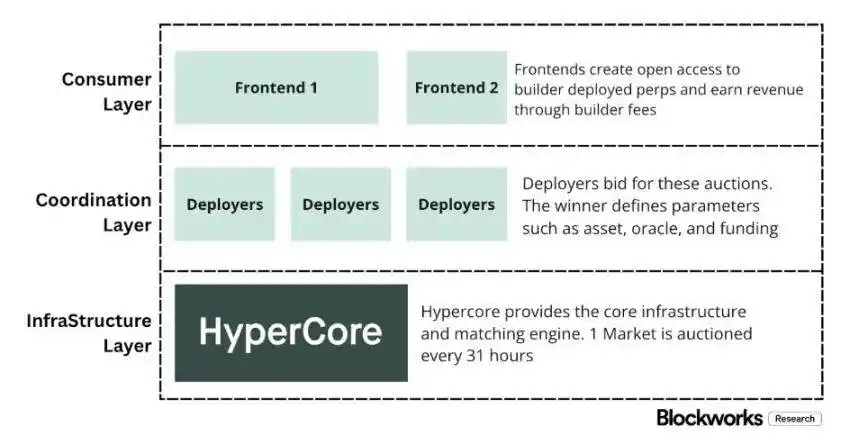

Hyperliquid's actual fee rate of 4 basis points is consistent with its strategic choice to position itself at the "market layer." The platform is building an "on-chain Nasdaq": through high-throughput order matching, margin calculation, and clearing technology stack (HyperCore), adopting a "market maker/taker" pricing model and providing market maker rebates—its core optimization direction is "trade execution quality" and "liquidity sharing," not "retail user profitability."

This positioning is reflected in two "TradFi-like" separation designs, which most cryptocurrency trading platforms have not adopted:

1. Permissionless Broker/Distribution Layer (Builder Codes)

"Builder Codes" allow third-party interfaces to connect to the core trading venue and set their own fee standards. Among them, the upper limit for third-party fees on perpetual contracts is 0.1% (10 basis points), 1% for spot, and fees can be set per order—this design creates a "distribution competition market," not a "single APP monopoly."

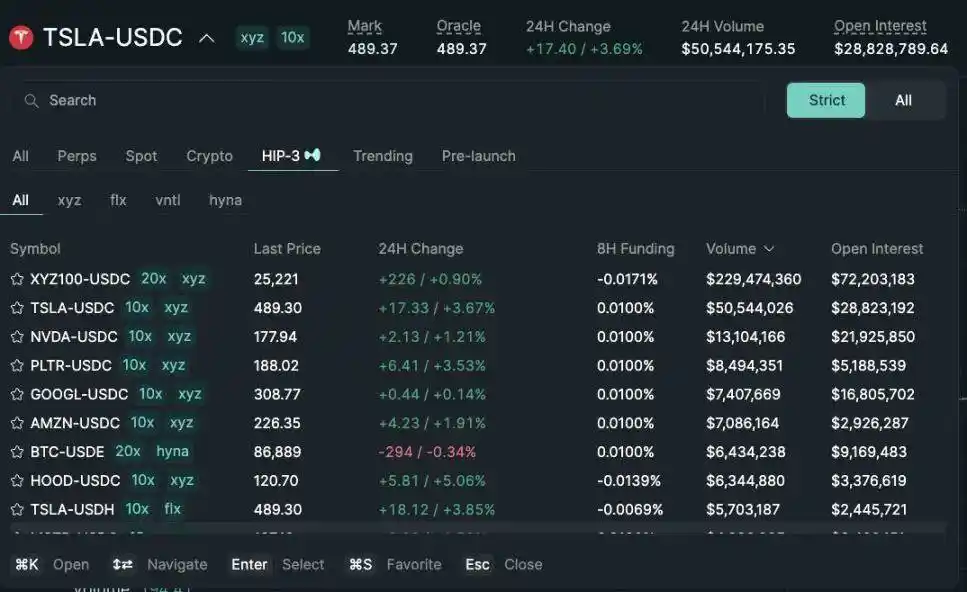

2. Permissionless Listing/Product Layer (HIP-3)

In traditional finance, exchanges control listing rights and product creation rights; HIP-3 "externalizes" this function: developers can deploy perpetual contracts based on the HyperCore technology stack and API, and independently define and operate trading markets. From an economic perspective, HIP-3 formally establishes a "revenue-sharing mechanism between the trading venue and the product party"—deployers of spot and HIP-3 perpetual contracts can receive 50% of the trading fees generated by the deployed assets.

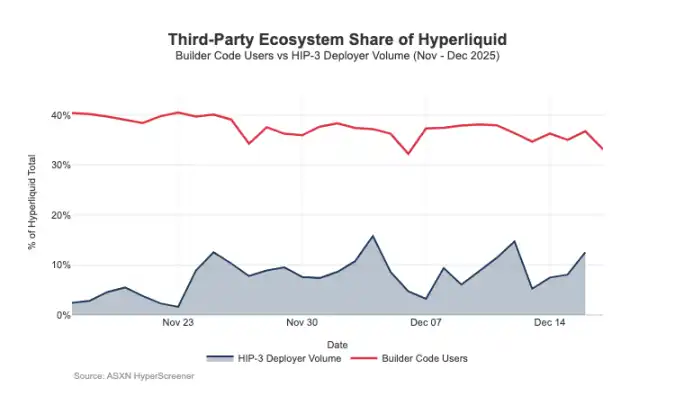

"Builder Codes" have already achieved results on the distribution end: as of mid-December, about 1/3 of users trade through third-party frontends, not the official interface.

However, this architecture also brings foreseeable pressure on the trading venue's fee revenue:

- Pricing compression: Multiple frontends share the same backend liquidity, and competition forces the "total cost" to the minimum; moreover, fees can be adjusted per order, further pushing pricing toward the bottom line;

- Loss of profit channels: Frontends control user account opening, service packaging, subscriptions, and trading processes, occupying the high-margin space of the "broker layer," while Hyperliquid only retains the low-margin income of the "trading venue layer";

- Strategic routing risk: If frontends develop into "cross-platform order routers," Hyperliquid will be forced into "wholesale execution competition"—needing to reduce fees or increase rebates to retain trading flow.

Through HIP-3 and Builder Codes, Hyperliquid has actively chosen a "low-margin market layer" positioning, while allowing a "high-margin broker layer" to form on top of it. If frontends continue to expand, they will gradually control "user-side pricing," "user retention channels," and "routing话语权," which will structurally pressure Hyperliquid's fee rates in the long run.

Defending Distribution Rights, Expanding Non-Exchange Profit Pools

The core risk Hyperliquid faces is the "commoditization trap": if third-party frontends can consistently attract users with prices lower than the official interface and eventually achieve "cross-platform routing," the platform will be forced to shift to a "wholesale execution economic model" (i.e., continuously narrowing profit margins).

Recent design adjustments indicate that Hyperliquid is trying to avoid this outcome while broadening its revenue sources beyond trading fees.

1. Distribution Defense: Maintaining the Economic Competitiveness of the Official Interface

Previously, Hyperliquid proposed that "staking HYPE tokens could enjoy up to a 40% fee discount"—this design would have structurally allowed third-party frontends to be "cheaper than the official interface." After canceling the proposal, external distribution channels lost the direct subsidy for "pricing below the official interface." Meanwhile, HIP-3 markets were initially only available through "developer distribution" and were not displayed on the official frontend; currently, these markets have been included in the official frontend's "strict list." This series of actions sends a clear signal: Hyperliquid retains the permissionless nature at the "developer layer" but is unwilling to compromise on "core distribution rights."

2. Stablecoin USDH: Shifting from "Trading Profit" to "Fund Pool Profit"

The core purpose of launching USDH is to recapture the "stablecoin reserve收益" that was previously flowing out. According to the public mechanism, reserve收益 are allocated 50% to Hyperliquid and 50% to USDH ecosystem development. Additionally, the design of "USDH trading markets enjoying fee discounts" further strengthens this logic: Hyperliquid is willing to sacrifice "single-trade profit compression" in exchange for "larger-scale, more stable fund pool profit"—essentially adding a "quasi-annuity income stream" that can grow based on the "monetary base" (not just relying on trading volume).

3. Portfolio Margin: Introducing "Institutional Broker-Style Financing Economics"

The "portfolio margin" mechanism unifies the margin calculation for spot and perpetual contracts, allows risk exposure hedging, and introduces "native lending loops." Hyperliquid charges "10% of the borrower's interest"—this design gradually ties the protocol's economic model to "leverage usage" and "interest rates," closer to the profit logic of a "broker/institutional broker" rather than a pure exchange model.

Hyperliquid's Path Toward a Broker Economic Model

Hyperliquid's trading throughput has reached "mainstream trading venue levels," but its profit model remains at the "market layer": nominal trading volume is huge, but the actual fee rate is only in the single-digit basis points. The gap with Coinbase and Robinhood is structural: retail platforms are at the "broker layer," controlling user relationships and balances, achieving high margins through diverse profit pools like "financing, idle funds, subscriptions"; pure trading venues focus on "trade execution as the core product," and due to liquidity competition and routing elasticity, "trade execution" inevitably becomes commoditized, with profit margins continuously compressed—Nasdaq is a classic example of this constraint in traditional finance.

Hyperliquid initially deeply fit the "trading venue prototype": by separating "distribution (Builder Codes)" and "product creation (HIP-3)," it rapidly drove ecosystem expansion and market coverage. But the cost of this architecture is "economic benefit outflow": if third-party frontends control "comprehensive pricing" and "cross-platform routing rights," Hyperliquid will face the risk of "becoming a wholesale channel, clearing trading flow with low margins."

However, recent actions indicate that the platform is consciously shifting toward "defending distribution rights" and "broadening revenue structure" (no longer relying solely on trading fees). For example, no longer subsidizing "external frontend price competition," incorporating HIP-3 markets into the official frontend, and adding "balance sheet-style profit pools." The launch of USDH is a typical case of incorporating "reserve收益" into the ecosystem (including 50% sharing and fee discounts); portfolio margin introduces "financing economics" by "charging 10% of borrower interest."

Currently, Hyperliquid is gradually moving toward a "hybrid model": based on the "trade execution channel,"叠加 "distribution defense" and "fund pool-driven profit pools." This transformation both reduces the risk of "falling into the wholesale low-margin trap" and moves closer to a "broker-style revenue structure" without abandoning the core advantages of "unified execution and clearing."

Looking ahead to 2026, the core question Hyperliquid faces is: How to move toward a "broker-style economy" without breaking the "outsourcing-friendly model"? USDH is the most direct test case—its current supply is about $100 million, this scale indicates: if the platform does not control "distribution rights," the expansion speed of "outsourced issuance" will be very slow. A more obvious alternative would have been "official interface default settings," such as automatically converting the approximately $4 billion USDC base funds into the native stablecoin (similar to Binance's model of automatically converting USDC to BUSD).

If Hyperliquid wants to capture "broker-level profit pools," it must take "broker-style actions": strengthen control, deepen the integration of self-operated products and the official interface, and clarify boundaries with ecosystem teams (avoiding internal competition over "distribution rights" and "fund balances").