Written by: @polarthedegen

Compiled by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

High Financialization and Markets

High financialization is the extreme stage of the financialization process, where financialization itself refers to the process of financial markets dominating the economy. In a highly financialized economy, speculative trading and other financial activities overshadow more socially beneficial productive services. At the same time, household wealth and inequality issues are increasingly tied to asset prices. In short, wealth is no longer directly linked to hard work and has also become disconnected from the means of production.

As a result, more capital flows into speculative activities, as Keynes once said:

"When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done." — John Maynard Keynes

Understanding markets is important. We live in (mostly) free-market economies: voluntary buyers and sellers meet here, prices are constantly updated to reflect new information, and in theory, winning traders continually replace losing traders. Their decisions determine how scarce resources are allocated in the market, thereby improving the market's allocative efficiency. In theory, the market is inherently meritocratic, which makes sense. Since traders decide where scarce resources go, we naturally want them to be good at allocating capital.

Therefore, in an idealized free-market system, skilled traders would direct capital toward socially desirable directions and be rewarded with more capital; those who are poor at allocation would have their capital reduced. Capital naturally flows to those with the strongest allocation capabilities, all while real output from manufacturing and services is simultaneously created.

But today, markets no longer fully achieve this. Trading was once an exclusive game. For a long time from the 19th to the 20th century, only well-connected individuals could participate, trading in venues like the New York Stock Exchange, limited to licensed brokers and members, with ordinary people having almost no access to the markets. Additionally, market data was difficult to obtain, leading to high information asymmetry.

Digitization changed all of this. With the proliferation of telephones and new technologies, emerging applications began to democratize investing. This has evolved to include apps like Robinhood, offering zero-commission trading and access to options, prediction markets, and cryptocurrencies. While this development has made investing more accessible and fairer, it has also increased the importance of markets in our daily lives.

Hyper-Gambling ⬄ High Financialization

The rapid digitization from the late 20th to the early 21st century has made financial speculation, or "hyper-gambling," not only unprecedentedly low-barrier but also participated in by a record number of people.

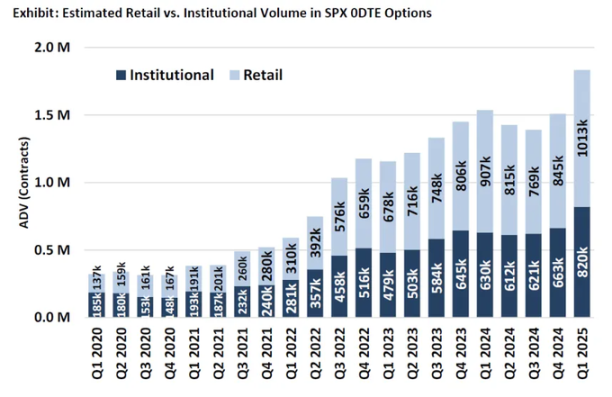

0-day-to-expiration options trading volume: can serve as a reference indicator for retail gambling behavior

One might ask, is the current level of high financialization a bad thing? I am almost certain: yes. Under high financialization, markets deviate from their fundamental role as "capital weighing machines" and merely become tools for making money. But I want to explore the causality more: we live in a society where both financialization and gambling are prominent, yet it is difficult to distinguish which is the cause and which is the effect.

Jez described hyper-gambling as a process where "real returns are compressed, and risk increases as compensation." I believe hyper-gambling is one of two natural responses to high financialization. But unlike the other response—the growing socialist tendencies among millennials—hyper-gambling catalyzes high financialization, which in turn raises the level of hyper-gambling, creating a near "ouroboros" cycle.

High financialization is a structural shift where society becomes increasingly reliant on markets; hyper-gambling is a behavioral response to the decoupling of effort and reward. Hyper-gambling itself is not a new phenomenon. A 1999 study showed that U.S. households with incomes below $10,000 spent 3% of their annual income on lottery tickets, motivated by the hope to "correct" their low-income status relative to peers. But in recent years, as society has become increasingly financialized (and digitized), the culture of gambling has become more prevalent.

Socialism as a Response

Now we can explore the first of the two natural responses to high financialization that I mentioned:

With the help of social media and digitization, financialization has permeated almost every aspect of our lives. Our lives increasingly revolve around markets, which now bear an unprecedented responsibility for capital allocation. The result is that young people can hardly get on the property ladder. The median age of property owners has hit a record high of 56, and the median age of first-time homebuyers has also reached 39, another historical high.

Asset prices have decoupled from real wages, partly due to inflation, making it nearly impossible for young people to accumulate capital. Peter Thiel pointed out that this is a significant reason for the rise of socialism:

"If a person is burdened with too much student debt, or housing is too expensive, they will be in a state of negative capital for a long time, making it difficult to start accumulating capital through real estate. If a person has no stake in the capitalist system, they are likely to oppose it."

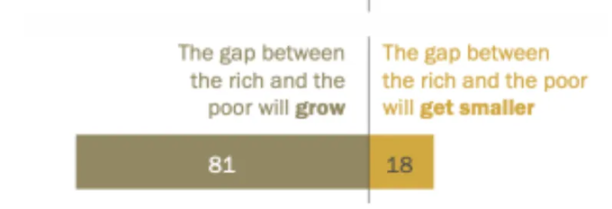

Asset inflation and high housing prices reduce the perceived social mobility. This feeling that the "social contract has been broken" is evident in a recent Wall Street Journal poll: only 31% of respondents still believe in the "American Dream"—that hard work leads to success. Moreover, most Americans believe the trend of financialization will continue until 2050, and the wealth gap will only widen.

This pessimism reinforces the notion that rising asset prices leave those without capital behind, and hard work cannot change this. When people no longer believe that hard work can improve their lives, they lose the motivation to work hard in a system they perceive as "rigged" and biased toward the bourgeoisie. This has cumulated into the rise of socialism today, a structural response to the increasing financialization of the world, aiming to re-establish the link between effort and reward through fairer asset distribution.

Socialism is an ideological response aimed at bridging the gap between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. However, as of May 2024, public trust in the government is only 22%, leading to the emergence of another natural response: more and more people, instead of relying on socialism to narrow the gap, are trying to join the upper class through (hyper-)gambling.

The Cycle

As mentioned earlier, the dream of turning one's life around through gambling is not new.

But with the advancement of the internet, the mechanics of gambling have completely changed. Today, almost anyone of any age can participate in gambling. Once socially ostracized behavior, now glorified by social media and with lowered barriers, has become deeply embedded in the social fabric.

As mentioned, the rise of gambling is a result of the internet's proliferation. Today, people don't need to go to physical casinos; gambling is everywhere. Anyone can open a Robinhood account to trade 0-day-to-expiration options; cryptocurrencies are equally accessible; online casino revenues are at historic highs.

As The New York Times put it:

"Today's gamblers are not just retirees at card tables but young men on smartphones. Thanks to a series of quasi-legal innovations in the online gambling industry, Americans can now bet on almost anything through investment accounts."

Recently, Google partnered with Polymarket to display betting odds in search results. The Wall Street Journal wrote: "Betting on football and elections is becoming as integrated into life as watching games and voting." While this is largely a social phenomenon, I believe its main driver is still high financialization. Even social gambling is a result of markets increasingly permeating our lives.

As household wealth becomes increasingly tied to asset prices, and wage growth lags, the upward mobility through hard work seems increasingly narrow. This raises a question: if one cannot improve their standard of living, why work hard? A recent study found that when families feel hopeless about buying a home, they tend to consume more, reduce work effort, and choose higher-risk investments. The same is true for low-wealth renters. These behaviors accumulate over the lifecycle, further widening the wealth gap between asset owners and non-owners.

At this point, survivorship bias starts to play a role. Stories of overnight riches on social media, conspicuous consumption on Instagram, and day traders鼓吹ing "quit your job" promises collectively foster a widespread speculative mentality. South Korea is a typical example: low perceived social mobility, worsening income inequality, high housing prices, leading to increased gambling tendencies among ordinary Koreans. The Financial Times reported: "Speculative retail investors have become the main force, accounting for more than half of the daily trading volume in South Korea's $2 trillion stock market." They call themselves the "Sampo Generation": giving up dating, marriage, and childbirth due to high youth unemployment, job instability, stagnant wages, high cost of living, heavy household debt, and fierce competition in education and job markets.

This phenomenon is not limited to South Korea; Japan's "Satori Generation" and China's "Lying Flat Generation" are similar.

Across the ocean in the U.S., half of men aged 18 to 49 have sports betting accounts, and 42% of Americans and 46% of Gen Z agree with the statement: "No matter how hard I work, I will never be able to buy a house I truly love." If a few minutes of betting could earn a week's, a month's, or even a year's salary, why bother doing a hated job for minimum wage? As Thiccy sharply pointed out:

"Technology has made speculation effortless, and social media spreads every story of overnight riches, luring the masses like moths to a flame into this certain-lose gamble."

The dopamine effect behind this cannot be underestimated. In the long run, these gamblers will lose money, but once they have experienced easy money, how can they return to a 9-to-5 job? People always think: just one more try, if only luck strikes one last time, then they can cash out and quit.

"You just need a dollar and a dream." — Classic slogan of the New York State Lottery

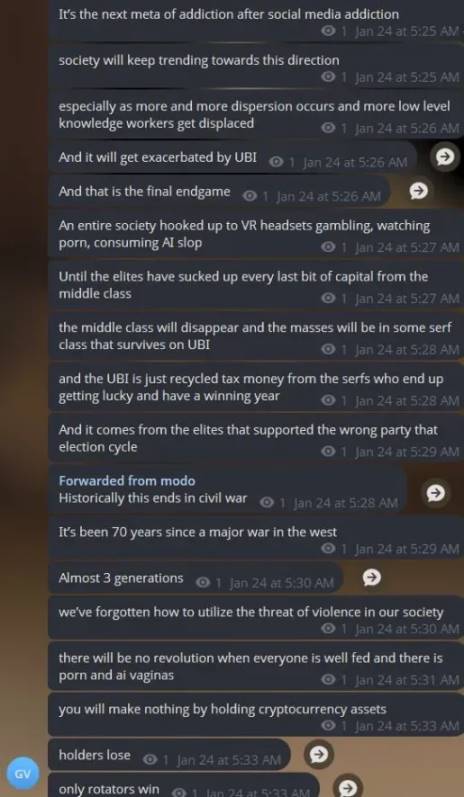

Thus, the ouroboros begins to cycle: high financialization triggers nihilism towards the system, leading to increased gambling, which in turn exacerbates financialization. More survivorship bias stories spread in the media, more people start gambling and lose money, resources are misallocated from productive behaviors. Markets no longer support companies that benefit society but flow to businesses that foster gambling. A stark example: HOOD (Robinhood) stock price rose 184% year-to-date, while the average retail investor spends only about 6 minutes researching per trade, often hastily before trading.

But I don't believe this is purely a market failure. The market is merely an extension of human nature, and human nature is full of flaws and selfishness. Therefore, the market chooses the most profitable outcome, not the one most beneficial to society. Even if it is detrimental to humanity in the long run, it should not be entirely blamed on market failure; the market is not a moral arbiter.

Nevertheless, it is sad that entire industries are built on swindling people out of their money. But as Milei said: "If you go to a casino and lose money, what can you complain about? You knew the nature of the casino." Or more bluntly: there are no tears in the casino. I do believe high financialization distorts markets. While markets are imperfect, financialization makes them increasingly resemble casinos. When net negative outcomes can be profitable, the problem clearly goes beyond the market itself.

Regardless of morality, this accelerates high financialization. Stock prices rise further, unemployment increases, escapism prevails—TikTok, Instagram Reels, the metaverse... The problem is that gambling is a zero-sum game (strictly speaking, due to fees, it's negative-sum). Even from a simple zero-sum perspective, it does not create new wealth or bring social benefits; it merely redistributes money. Less and less capital flows into innovation, development, and positive-sum outcomes. Elon Musk once said: "The meaning of civilization is to create far more than it consumes." But in a highly financialized society, this is difficult to achieve because we also have to deal with another consequence of financialization: escapism.

The gap between the middle and upper classes in leisure activities has never been smaller, as humans spend more and more time online. This, combined with declining social mobility, not only weakens the motivation to work hard but also reduces the desire to create beautiful new things.

What I want to say is: in a highly financialized society, an individual cannot create more than they consume, and society thus struggles to achieve a positive-sum outcome.

Finally, I end with this description of a highly financialized techno-capitalist society: